4.1 The Globalization of Business

Adapted by Stephen Skripak with Ron Poff

Do you wear Nike shoes or Timberland boots? Buy groceries at Giant Stores or Stop & Shop? Listen to Halsey, Billie Eilish, or Drake on Spotify? If you answered yes to any of these questions, you’re a global business customer. Both Nike and Timberland manufacture most of their products overseas. The Dutch firm Royal Ahold owns all three supermarket chains. And Spotify is a Swedish enterprise.

Take an imaginary walk down Orchard Road, the most fashionable shopping area in Singapore. You’ll pass department stores such as Tokyo-based Takashimaya and London’s very British Marks & Spencer, both filled with such well-known international labels as Ralph Lauren Polo, Burberry, and Chanel. If you need a break, you can also stop for a latte at Seattle-based Starbucks.

When you’re in the Chinese capital of Beijing, don’t miss Tiananmen Square. Parked in front of the Great Hall of the People, the seat of Chinese government, are fleets of black Buicks, cars made by General Motors in Flint, Michigan. If you’re adventurous enough to find yourself in Faisalabad, a medium-size city in Pakistan, you’ll see Hamdard University, located in a refurbished hotel. Step inside its computer labs, and the sensation of being in a faraway place will likely disappear: on the computer screens, you’ll recognize the familiar Microsoft flag—the same one emblazoned on screens in Microsoft’s hometown of Seattle and just about everywhere else on the planet.

The Globalization of Business

The globalization of business is bound to affect you. Not only will you buy products manufactured overseas, but it’s highly likely that you’ll meet and work with individuals from various countries and cultures as customers, suppliers, colleagues, employees, or employers. The bottom line is that the globalization of world commerce has an impact on all of us. Therefore, it makes sense to learn more about how globalization works. Although globalization has been the trend towards increased connections and interdependence in the world’s economies, there has been talk about nationalism from the impact of COVID-19 and trade agreements. However, this has yet to be determined, therefore, this chapter will focus on globalization as defined above.

Never before has business spanned the globe the way it does today. But why is international business important? Why do companies and nations engage in international trade? What strategies do they employ in the global marketplace? How do governments and international agencies promote and regulate international trade? These questions and others will be addressed in this chapter. Let’s start by looking at the more specific reasons why companies and nations engage in international trade.

Why Do Nations Trade?

Why does the United States import automobiles, steel, digital phones, and apparel from other countries? Why don’t we just make them ourselves? Why do other countries buy wheat, chemicals, machinery, and consulting services from us? Because no national economy produces all the goods and services that its people need. In fact, countries have been trading for thousands of years. Marco Polo established trade between Europe and China in the late thirteenth century, introducing gun powder to China and citrus and spices to Europe.[1] Countries are importers when they buy goods and services from other countries; when they sell products to other nations, they’re exporters. (We’ll discuss importing and exporting in greater detail later in the chapter.) The monetary value of international trade is enormous. In 2018, the total value of worldwide trade in merchandise and commercial services was $19.5 trillion. In comparison, this figure stood at around 6.45 trillion US dollars in 2000.[2]

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

To understand why certain countries import or export certain products, you need to realize that every country (or region) can’t produce the same products. The cost of labor, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world. Most economists use the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage to explain why countries import some products and export others.

Absolute Advantage

A nation has an absolute advantage if (1) it’s the only source of a particular product or (2) it can make more of a product using fewer resources than other countries. Because of climate and soil conditions, for example, France had an absolute advantage in wine making until its dominance of worldwide wine production was challenged by the growing wine industries in Italy, Spain, and the United States. Unless an absolute advantage is based on some limited natural resource, it seldom lasts. That’s why there are few, if any, examples of absolute advantage in the world today.

Comparative Advantage

How can we predict, for any given country, which products will be made and sold at home, which will be imported, and which will be exported? This question can be answered by looking at the concept of comparative advantage, which exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost compared to another nation. But what’s an opportunity cost? Opportunity costs are the products that a country must forego making in order to produce something else. When a country decides to specialize in a particular product, it must sacrifice the production of another product. Countries benefit from specialization—focusing on what they do best, and trading the output to other countries for what those countries do best. The United States, for instance, is increasingly an exporter of knowledge-based products, such as software, movies, music, and professional services (management consulting, financial services, and so forth). America’s colleges and universities, therefore, are a source of comparative advantage, and students from all over the world come to the United States for the world’s best higher-education system.

France and Italy are centers for fashion and luxury goods and are leading exporters of wine, perfume, and designer clothing. Japan’s engineering expertise has given it an edge in such fields as automobiles and consumer electronics. And with large numbers of highly skilled graduates in technology, India has become the world’s leader in low-cost, computer-software engineering.

How Do We Measure Trade Between Nations?

To evaluate the nature and consequences of its international trade, a nation looks at two key indicators. We determine a country’s balance of trade by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favorable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavorable balance, or a trade deficit.

For many years, the United States has had a trade deficit: we buy far more goods from the rest of the world than we sell overseas. This fact shouldn’t be surprising. With high income levels, we not only consume a sizable portion of our own domestically produced goods but enthusiastically buy imported goods. Other countries, such as China and Taiwan, which manufacture high volumes for export, have large trade surpluses because they sell far more goods overseas than they buy.

Managing the National Credit Card

Are trade deficits a bad thing? Not necessarily. They can be positive if a country’s economy is strong enough both to keep growing and to generate the jobs and incomes that permit its citizens to buy the best the world has to offer. That was certainly the case in the United States in the 1990s. Some experts, however, are alarmed at our trade deficit. Investment guru Warren Buffet, for example, cautions that no country can continuously sustain large and burgeoning trade deficits. Why not? Because creditor nations will eventually stop taking IOUs from debtor nations, and when that happens, the national spending spree will have to cease. “Our national credit card,” he warns, “allows us to charge truly breathtaking amounts. But that card’s credit line is not limitless.”[3]

By the same token, trade surpluses aren’t necessarily good for a nation’s consumers. Japan’s export-fueled economy produced high economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s. But most domestically made consumer goods were priced at artificially high levels inside Japan itself—so high, in fact, that many Japanese traveled overseas to buy the electronics and other high-quality goods on which Japanese trade was dependent.

CD players and televisions were significantly cheaper in Honolulu or Los Angeles than in Tokyo. How did this situation come about? Though Japan manufactures a variety of goods, many of them are made for export. To secure shares in international markets, Japan prices its exported goods competitively. Inside Japan, because competition is limited, producers can put artificially high prices on Japanese-made goods. Due to a number of factors (high demand for a limited supply of imported goods, high shipping and distribution costs, and other costs incurred by importers in a nation that tends to protect its own industries), imported goods are also expensive.[4]

Balance of Payments

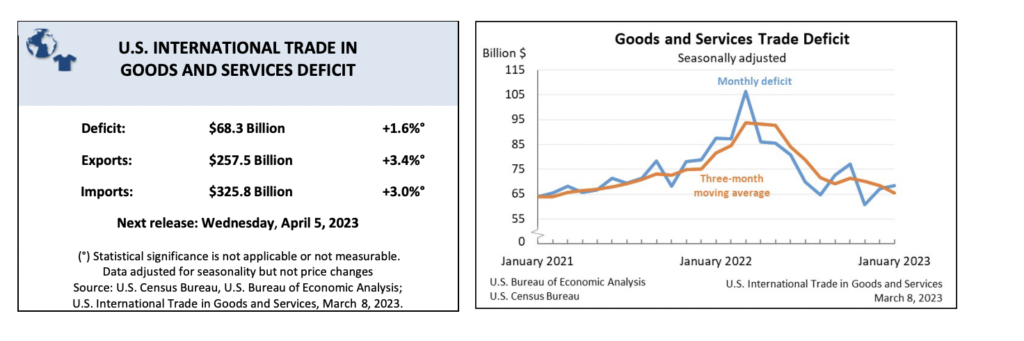

The second key measure of the effectiveness of international trade is balance of payments: the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow of money coming into a country and the total flow of money going out. As in its balance of trade, the biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that flows as a result of imports and exports. But balance of payments includes other cash inflows and outflows, such as cash received from or paid for foreign investment, loans, tourism, military expenditures, and foreign aid. For example, if a US company buys some real estate in a foreign country, that investment counts in the US balance of payments, but not in its balance of trade, which measures only import and export transactions. In the long run, having an unfavorable balance of payments can negatively affect the stability of a country’s currency. The United States has experienced unfavorable balances of payments since the 1970s which has forced the government to cover its debt by borrowing from other countries.[5] Figure 4.2 provides an overview of the ongoing goods and services trade deficit.

Key Takeaways

- Nations trade because they don’t produce all the products that their inhabitants need.

- The cost of labor, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world, so not every country has the same resources or is good at producing the same products.

- To explain how countries decide what products to import and export, economists use the concepts of absolute and comparative advantage: A nation has an absolute advantage if it’s the only source of a particular product or can make more of a product with the same amount of or fewer resources than other countries. A comparative advantage exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost than other nations.

- We determine a country’s balance of trade by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favorable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavorable balance, or a trade deficit.

- The balance of payments is the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow coming into a country and the total flow going out. The biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that comes in and goes out as a result of exports and imports.

- Silk Road Foundation (n.d.). "Marco Polo and His Travels." Silk Road Foundation. Retrieved from: http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/artl/marcopolo.shtml#:~:text=Marco Polo (1254-1324),predecessors, beyond Mongolia to China. ↵

- Liam O'Connell (2019). "Worldwide Export Trade Volume 1950-2018." Statistica. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264682/worldwide-export-volume-in-the-trade-since-1950/ ↵

- Warren E. Buffet and Carol Loomis (2003). “America's Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling The Nation Out From Under Us. Here's A Way To Fix The Problem—And We Need To Do It Now.” Fortune. Retrieved from: http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/11/10/352872/index.htm ↵

- Anonymous (2003). “Why Are Prices in Japan So Damn High?” The Japan FAQ.com. Retrieved from: http://www.thejapanfaq.com/FAQ-Prices.html ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau (2015). “U.S. Trade in Goods and Services—Balance of Payments (BOP) Basis, 1960 thru 2014.” Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/gands.txt ↵