4.2 Opportunities in International Business

Adapted by Stephen Skripak with Ron Poff

The fact that nations exchange billions of dollars in goods and services each year demonstrates that international trade makes good economic sense. For a company wishing to expand beyond national borders, there are a variety of ways it can get involved in international business. Let’s take a closer look at the more popular ones.

Importing and Exporting

Importing (buying products overseas and reselling them in one’s own country) and exporting (selling domestic products to foreign customers) are the oldest and most prevalent forms of international trade. For many companies, importing is the primary link to the global market. American food and beverage wholesalers, for instance, import for resale in US supermarkets the bottled waters Evian and Fiji from their sources in the French Alps and the Fiji Islands respectively.[1] Other companies get into the global arena by identifying an international market for their products and becoming exporters. The Chinese, for instance, are fond of fast foods cooked in soybean oil. Because they also have an increasing appetite for meat, they need high-protein soybeans to raise livestock.[2] American farmers exported over $9 billion worth of soybeans to China in 2010 to nearly $21 billion in 2017.[3]

Licensing and Franchising

A company that wants to get into an international market quickly while taking only limited financial and legal risks might consider licensing agreements with foreign companies. An international licensing agreement allows a foreign company (the licensee) to sell the products of a producer (the licensor) or to use its intellectual property (such as patents, trademarks, copyrights) in exchange for what is known as royalty fees. Here’s how it works: You own a company in the United States that sells coffee-flavored popcorn. You’re sure that your product would be a big hit in Japan, but you don’t have the resources to set up a factory or sales office in that country. You can’t make the popcorn here and ship it to Japan because it would get stale. So you enter into a licensing agreement with a Japanese company that allows your licensee to manufacture coffee-flavored popcorn using your special process and to sell it in Japan under your brand name. In exchange, the Japanese licensee would pay you a royalty fee—perhaps a percentage of each sale or a fixed amount per unit.

Another popular way to expand overseas is to sell franchises. Under an international franchise agreement, a company (the franchiser) grants a foreign company (the franchisee) the right to use its brand name and to sell its products or services. The franchisee is responsible for all operations but agrees to operate according to a business model established by the franchiser. In turn, the franchiser usually provides advertising, training, and new-product assistance. Franchising is a natural form of global expansion for companies that operate domestically according to a franchise model, including restaurant chains, such as McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, and hotel chains, such as Holiday Inn and Best Western.

Contract Manufacturing and Outsourcing

Because of high domestic labor costs, many US companies manufacture their products in countries where labor costs are lower. This arrangement is called international contract manufacturing, a form of outsourcing. A US company might contract with a local company in a foreign country to manufacture one of its products. It will, however, retain control of product design and development and put its own label on the finished product. Contract manufacturing is quite common in the US apparel business, with most American brands being made in a number of Asian countries, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.[4]

Thanks to twenty-first-century information technology, non-manufacturing functions can also be outsourced to nations with lower labor costs. US companies increasingly draw on a vast supply of relatively inexpensive skilled labor to perform various business services, such as software development, accounting, and claims processing. For years, American insurance companies have processed much of their claims-related paperwork in Ireland. With a large, well-educated population with English language skills, India has become a center for software development and customer-call centers for American companies. In the case of India, as you can see in Figure 4.5, the attraction is not only a large pool of knowledge workers but also significantly lower wages.

| Occupation | US Wage per Hour (per year) | Indian Wage per Hour (per year) |

|---|---|---|

| Accountant | $37.14 per hour (~$77,250 per year) | $1.91 per hour (~$4784 per year) |

| Computer Systems Analyst | $47.73 per hour (~$99,270 per year) | $4.88 per hour (~$12,174 per year) |

| Cleaner | $16.51 per hour (~$34,350 per year) | $.94 per hour (~$2337 per year) |

Strategic Alliances and Joint Ventures

What if a company wants to do business in a foreign country but lacks the expertise or resources? Or what if the target nation’s government doesn’t allow foreign companies to operate within its borders unless it has a local partner? In these cases, a firm might enter into a strategic alliance with a local company or even with the government itself.

A strategic alliance is an agreement between two companies (or a company and a nation) to pool resources in order to achieve business goals that benefit both partners. For example, Korean automaker Hyundai Motor Co agreed to jointly develop electric vehicles with California startup Canoo in addition to investing $110 million in UK startup Arrival to jointly develop electric commercial vehicles. [5]

An alliance can serve a number of purposes:

- Enhancing marketing efforts

- Building sales and market share

- Improving products

- Reducing production and distribution costs

- Sharing technology

Alliances range in scope from informal cooperative agreements to joint ventures—alliances in which the partners fund a separate entity (perhaps a partnership or a corporation) to manage their joint operation. Magazine publisher Hearst, for example, has joint ventures with companies in several countries. So, young women in Israel can read Cosmo Israel in Hebrew, and Russian women can pick up a Russian-language version of Cosmo that meets their needs. The US edition serves as a starting point to which nationally appropriate material is added in each different nation. This approach allows Hearst to sell the magazine in more than 50 countries.[6]

Foreign Direct Investment and Subsidiaries

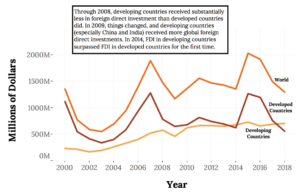

Many of the approaches to global expansion that we’ve discussed so far allow companies to participate in international markets without investing in foreign plants and facilities. As markets expand, however, a firm might decide to enhance its competitive advantage by making a direct investment in operations conducted in another country. Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil—the building of factories, sales offices, and distribution networks to serve local markets in a nation other than the company’s home country. On the other hand, offshoring occurs when the facilities set up in the foreign country replace US manufacturing facilities and are used to produce goods that will be sent back to the United States for sale. Shifting production to low-wage countries is often criticized as it results in the loss of jobs for US workers.[7]

FDI is generally the most expensive commitment that a firm can make to an overseas market, and it’s typically driven by the size and attractiveness of the target market. For example, German and Japanese automakers, such as BMW, Mercedes, Toyota, and Honda, have made serious commitments to the US market: most of the cars and trucks that they build in plants in the South and Midwest are destined for sale in the United States.

A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary: an independent company owned by a foreign firm (called the parent). This approach to going international not only gives the parent company full access to local markets but also exempts it from any laws or regulations that may hamper the activities of foreign firms. The parent company has tight control over the operations of a subsidiary, but while senior managers from the parent company often oversee operations, many managers and employees are citizens of the host country. Not surprisingly, most very large firms have foreign subsidiaries. IBM and Coca-Cola, for example, have both had success in the Japanese market through their foreign subsidiaries (IBM–Japan and Coca-Cola–Japan). FDI goes in the other direction, too, and many companies operating in the United States are in fact subsidiaries of foreign firms. Gerber Products, for example, is a subsidiary of the Swiss company Novartis, while Stop & Shop and Giant Food Stores belong to the Dutch company Royal Ahold. Where does most FDI capital end up? Figure 4.6 provides an overview of amounts, destinations (high to low income countries), and trends.

All these strategies have been employed successfully in global business. But success in international business involves more than finding the best way to reach international markets. Global business is a complex, risky endeavor. Over time, many large companies reach the point of becoming truly multi-national.

| Rank | Company | Country | Revenues ($ Mil.) | Revenue (% Change) | Profits ($ Mil.) | Profits (% Change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Walmart | U.S. | $572,754 | $485.7 | $485.7 | $514.4 |

| 2. | Amazon | U.S. | $469,822 | $446.8 | $446.8 | $414.6 |

| 3. | State Grid | China | $460,617 | $431.3 | $431.3 | $396.6 |

| 4. | China National Petroleum | China | $411,693 | $428.6 | $428.6 | $393 |

| 5. | Sinopec Group | China | $401,314 | $339.4 | $339.4 | $387.1 |

| 6. | Saudi Aramco | Saudi Arabia | $400,399 | N/A* | N/A* | $355.9 |

| 7. | Apple | U.S. | $365,817 | $358.7 | $358.7 | $303.7 |

| 8. | Volkswagen | Germany | $295,820 | $382.6 | $382.6 | $290.2 |

| 9. | China State Construction Engineering | China | $293,712 | $268.6 | $268.6 | $278.3 |

| 10. | Volkswagen | U.S. | $292,111 | $247.7 | $247.7 | $272.6 |

Multinational Corporations

A company that operates in many countries is called a multinational corporation (MNC). Fortune magazine’s roster of the top 500 MNCs speaks for the growth of non-US businesses. Only two of the top 10 MNCs are headquartered in the US (see Figure 5.6 above): Wal-Mart (number 1) and Exxon (number 8). Four others are in the top 15: Apple, Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon, and UnitedHealth Group. The others are non-US firms. Interestingly, of the 15 top companies, seven are energy suppliers, two are motor vehicle companies, and two are consumer electronics or computer companies. Also interesting is the difference between company revenues and profits: the list would look quite different arranged by profits instead of revenues!

MNCs often adopt the approach encapsulated in the motto “Think globally, act locally.” They often adjust their operations, products, marketing, and distribution to mesh with the environments of the countries in which they operate. Because they understand that a “one-size-fits-all” mentality doesn’t make good business sense when they’re trying to sell products in different markets, they’re willing to accommodate cultural and economic differences. Increasingly, MNCs supplement their mainstream product line with products designed for local markets. Coca-Cola, for example, produces coffee and citrus-juice drinks developed specifically for the Japanese market.[8] When Nokia and Motorola design cell phones, they’re often geared to local tastes in color, size, and other features. For example, Nokia introduced a cell phone for the rural Indian consumer that has a dust-resistant keypad, anti-slip grip, and a built-in flashlight.[9] McDonald’s provides a vegetarian menu in India, where religious convictions affect the demand for beef and pork.[10] In Germany, McDonald’s caters to local tastes by offering beer in some restaurants and a Shrimp Burger in Hong Kong and Japan.[11]

Likewise, many MNCs have made themselves more sensitive to local market conditions by decentralizing their decision making. While corporate headquarters still maintain a fair amount of control, home-country managers keep a suitable distance by relying on modern telecommunications. Today, fewer managers are dispatched from headquarters; MNCs depend instead on local talent. Not only does decentralized organization speed up and improve decision making, but it also allows an MNC to project the image of a local company. IBM, for instance, has been quite successful in the Japanese market because local customers and suppliers perceive it as a Japanese company. Crucial to this perception is the fact that the vast majority of IBM’s Tokyo employees, including top leadership, are Japanese nationals.[12]

Criticism of MNCs

The global reach of MNCs is a source of criticism as well as praise. Critics argue that they often destroy the livelihoods of home-country workers by moving jobs to developing countries where workers are willing to labor under poor conditions and for less pay. They also contend that traditional lifestyles and values are being weakened, and even destroyed, as global brands foster a global culture of American movies; fast food; and cheap, mass-produced consumer products. Still others claim that the demand of MNCs for constant economic growth and cheaper access to natural resources do irreversible damage to the physical environment. All these negative consequences, critics maintain, stem from the abuses of international trade—from the policy of placing profits above people, on a global scale. These views surfaced in violent street demonstrations in Seattle in 1999 and Genoa, Italy, in 2000, and since then, meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank have regularly been assailed by protestors.

In Defense of MNCs

Supporters of MNCs respond that huge corporations deliver better, cheaper products for customers everywhere; create jobs; and raise the standard of living in developing countries. They also argue that globalization increases cross-cultural understanding. Anne O. Kruger, first deputy managing director of the IMF, says the following:

“The impact of the faster growth on living standards has been phenomenal. We have observed the increased well-being of a larger percentage of the world’s population by a greater increment than ever before in history. Growing incomes give people the ability to spend on things other than basic food and shelter, in particular on things such as education and health. This ability, combined with the sharing among nations of medical and scientific advances, has transformed life in many parts of the developing world.

Infant mortality has declined from 180 per 1,000 births in 1950 to 60 per 1,000 births. Literacy rates have risen from an average of 40 percent in the 1950s to over 70 percent today. World poverty has declined, despite still-high population growth in the developing world.”[13]

Key Takeaways

- A company that operates in many countries is called a multinational corporation (MNC).

- For a company in the United States wishing to expand beyond national borders, there are a variety of ways to get involved in international business:

- Importing involves purchasing products from other countries and reselling them in one’s own.

- Exporting entails selling products to foreign customers.

- Under a franchise agreement, a company grants a foreign company the right to use its brand name and sell its products.

- A licensing agreement allows a foreign company to sell a company’s products or use its intellectual property in exchange for royalty fees.

- Through international contract manufacturing, or outsourcing, a company has its products manufactured or services provided in other countries.

- A joint venture is a type of strategic alliance in which a separate entity funded by the participating companies is formed.

- Foreign direct investment (FDI) refers to the formal establishment of business operations on foreign soil.

- A common form of FDI is the foreign subsidiary, an independent company owned by a foreign firm.

- Success in international business requires an understanding an assortment of cultural, economic, and legal/regulatory differences between countries. Cultural challenges stem from differences in language, concepts of time and sociability, and communication styles.

- Fine Waters Media (2016). “Bottled Waters of France.” Retrieved from: http://www.finewaters.com/bottled-waters-of-the-world/france/evian; Fiji Water (2016). “Fiji water history.” Retrieved from: https://store.fijiwater.com/about-fiji-water-bottle-delivery ↵

- H. Frederick Gale (2003). “China’s Growing Affluence: How Food Markets Are Responding.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2003-june/chinas-growing-affluence.aspx#.Vz-JUfkrIqM ↵

- Wall Street Journal (2019). “Farmers Built a Soybean Export Empire Around China. Now They’re Fighting to Save It.” Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/farmers-built-a-soybean-export-empire-around-china-now-theyre-fighting-to-save-it-11562260248#:~:text=The customer is China and,obscure crop into a blockbuster. ↵

- Gary Gereffi and Stacey Frederick (2010). “The Global Apparel Value Chain, Trade and the Crisis: Challenges and Opportunities for Developing Countries.” World Bank. Retrieved from: http://www19.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2010/05413.pdf ↵

- Paul Lienert and Joyce Lee (2020). "Hyundai Signs Development Deal With Another Electric Wehicle Startup." Reuters. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-autos-hyundai-motor-electric-idUSKBN2052MI ↵

- Clothing, Makeup and Beauty Tips (2012). Lihi Griner Cosmopolitan Israel. Retrieved from: http://www.magxone.com/cosmopolitan/lihi-griner-cosmopolitan-israel-may-2012/attachment/lihi-griner-cosmopolitan-israel/; CountryMagazines.Blogspot.com (2015). Retrieved from: http://country-magazines.blogspot.com/2015/09/tennis-maria-sharapova-cosmopolitan.html ↵

- Michael Mandel (2007). “The Real Cost of Offshoring.” Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2007-06-17/the-real-cost-of-offshoring ↵

- James C. Morgan and Jeffrey Morgan (1991). Cracking the Japanese Market. New York: Free Press. p. 102. ↵

- Case Study Inc. (2010). “Glocalization Examples—Think Globally and Act Locally.” CaseStudyInc.com. Retrieved from: http://www.casestudyinc.com/glocalization-examples-think-globally-and-act-locally ↵

- McDonald’s India (n.d.). “McDonald’s India.” Retrieved from: http://www.mcdonaldsindia.com/McDonaldsinIndia.pdf ↵

- Susan L. Nasr (2009). "10 Unusual Items from McDonald's International Menu." HowStuffWorks. Retrieved from: http://money.howstuffworks.com/10-items-from-mcdonalds-international-menu5.htm ↵

- James C. Morgan and J. Jeffrey Morgan (1991). Cracking the Japanese Market. New York: Free Press. p. 117. ↵

- Anne O. Krueger (2002). “Supporting Globalization.” Eisenhower National Security Conference: “National Security for the 21st Century: Anticipating Challenges, Seizing Opportunities, Building Capabilities.” Retrieved from: http://www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/2002/092602a.htm ↵