9.5 Equity Theory

Adapted by Stephen Skripak with Ron Poff

What if you spent 30 hours working on a class report, did everything you were supposed to do, and handed in an excellent assignment (in your opinion). Your roommate, on the other hand, spent about five hours and put everything together at the last minute. You know, moreover, that he ignored half the requirements and never even ran his assignment through a spell-checker. A week later, your teacher returns the reports. You get a C and your roommate gets a B . In all likelihood, you’ll feel that you’ve been treated unfairly relative to your roommate.

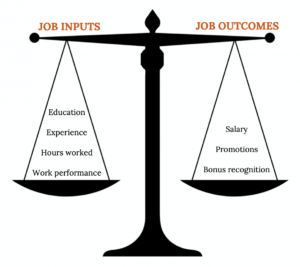

Your reaction makes sense according to the , which focuses on our perceptions of how fairly we’re treated relative to others. Applied to the work environment, this theory proposes that employees analyze their contributions or job inputs (hours worked, education, experience, work performance) and their rewards or job outcomes (salary, bonus, promotion, recognition). Then they create a contributions/rewards ratio and compare it to those of other people. The basis of comparison can be any one of the following:

- Someone in a similar position.

- Someone holding a different position in the same organization.

- Someone with a similar occupation.

- Someone who shares certain characteristics (such as age, education, or level of experience).

- Oneself at another point in time.

When individuals perceive that the ratio of their contributions to rewards is comparable to that of others, they perceive that they’re being treated fairly or equitably; when they perceive that the ratio is out of balance, they perceive inequity. Occasionally, people will perceive that they’re being treated better than others. More often, however, they conclude that others are being treated better (and that they themselves are being treated worse). This is what you concluded when you saw your grade in the previous example. You’ve calculated your ratio of contributions (hours worked, research and writing skills) to rewards (project grade), compared it to your roommate’s ratio, and concluded that the two ratios are out of balance.

What will an employee do if he or she perceives an inequity? The individual might try to bring the ratio into balance, either by decreasing inputs (working fewer hours, not taking on additional tasks) or by increasing outputs (asking for a raise). If this strategy fails, an employee might complain to a supervisor, transfer to another job, leave the organization, or rationalize the situation (e.g., deciding that the situation isn’t so bad after all). Equity theory advises managers to focus on treating workers fairly, especially in determining compensation, which is, naturally, a common basis of comparison.

Key Takeaways

- Equity theory focuses on our perceptions of how fairly we are treated relative to others. This theory proposes that employees create rewards ratios that they compare to those of others and will be less motivated when they perceive an imbalance in treatment.

which focuses on our perceptions of how fairly we’re treated relative to others