3.1 “Mommy, Why Do You Have to Go to Jail?”

The one question Betty Vinson would have preferred to avoid is “Mommy, why do you have to go to jail?” (Pullman, 2003). Vinson graduated with an accounting degree from Mississippi State and married her college sweetheart. After a series of jobs at small banks, she landed a mid-level accounting job at WorldCom, at the time still a small long-distance provider. Sparked by the telecom boom, however, WorldCom soon became a darling of Wall Street, and its stock price soared. Now working for a wildly successful company, Vinson rounded out her life by reading legal thrillers and watching her daughter play soccer.

Her moment of truth came in mid-2000, when company executives learned that profits had plummeted. They asked Vinson to make some accounting adjustments to boost income by $828 million. Vinson knew that the scheme was unethical (at the very least) but she gave in and made the adjustments. Almost immediately, she felt guilty and told her boss that she was quitting. When news of her decision came to the attention of CEO Bernard Ebbers and CFO Scott Sullivan, they hastened to assure Vinson that she’d never be asked to cook any more books. Sullivan explained it this way: “We have planes in the air. Let’s get the planes landed. Once they’ve landed, if you still want to leave, then leave. But not while the planes are in the air” (Pullman, 2003). Besides, she’d done nothing illegal, and if anyone asked, he’d take full responsibility. So Vinson decided to stay. After all, Sullivan was one of the top CFOs in the country; at age thirty-seven, he was already making $19 million a year (Ripley, 2002). Who was she to question his judgment? (Clabaugh, 2005)

Six months later, Ebbers and Sullivan needed another adjustment—this time for $771 million. This scheme was even more unethical than the first: it entailed forging dates to hide the adjustment. Pretty soon, Vinson was making adjustments on a quarterly basis—first for $560 million, then for $743 million, and yet again for $941 million. Eventually, Vinson had juggled almost $4 billion, and before long, the stress started to get to her: she had trouble sleeping, lost weight, and withdrew from people at work. She decided to hang on when she got a promotion and a $30,000 raise.

By spring 2002, however, it was obvious that adjusting the books was business as usual at WorldCom. Vinson finally decided that it was time to move on, but, unfortunately, an internal auditor had already put two and two together and blown the whistle. The Securities and Exchange Commission charged WorldCom with fraud amounting to $11 billion—the largest in U.S. history. Seeing herself as a valuable witness, Vinson was eager to tell what she knew. The government, however, regarded her as more than a mere witness. When she was named a co-conspirator, she agreed to cooperate fully and pleaded guilty to criminal conspiracy and securities fraud. But she won’t be the only one doing time: Scott Sullivan will be in jail for five years, and Bernie Ebbers will be locked up for twenty-five years. Both maintain that they are innocent (Reeves, 2005 and Andelman, 2005).

So where did Betty Vinson, mild-mannered midlevel executive and mother, go wrong? How did she manage to get involved in a scheme that not only bilked investors out of billions but also cost seventeen thousand people their jobs? (Pullman, 2003) Ultimately, of course, we can only guess. Maybe she couldn’t say no to her bosses; perhaps she believed that they’d take full responsibility for her accounting “adjustments.” Possibly she was afraid of losing her job or didn’t fully understand the ramifications of what she was doing. What we do know is that she disgraced herself and went to jail (Hancock, 2002).

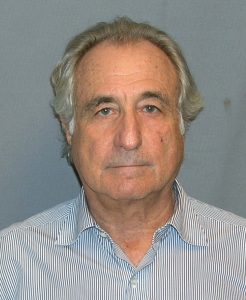

The WorldCom situation is not an isolated incident. Perhaps you have heard of Bernie Madoff, founder of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities and former chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange (Time Magazine, 2009). Madoff is alleged to have run a giant Ponzi scheme that cheated investors of up to $65 billion (Langan ,2008). His wrongdoings won him a spot at the top of Time Magazine’s Top 10 Crooked CEOs. According to the SEC charges, Madoff convinced investors to give him large sums of money. In return, he gave them an impressive 8 percent to 12 percent return a year. But Madoff never really invested their money. Instead, he kept it for himself. He got funds to pay the first investors their return (or their money back if they asked for it) by bringing in new investors. Everything was going smoothly until the fall of 2008, when the stock market plummeted and many of his investors asked for their money. As he no longer had it, the game was over and he had to admit that the whole thing was just one big lie. Thousands of investors, including many of his wealthy friends, not-so-rich retirees who trusted him with their life savings, and charitable foundations, were financially ruined. Those harmed by Madoff either directly or indirectly were likely pleased when he was sentenced to jail for one-hundred and fifty years.

References

This case is based on Susan Pullman (2003). “How Following Orders Can Harm Your Career.” The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: CFO.com. http://ww2.cfo.com/human-capital-careers/2003/10/how-following-orders-can-harm-your-career/

David A. Andelman (2005). “Scott Sullivan Gets Slap on the Wrist—WorldCom Rate Race.” Forbes. Retrieved from: mindfully.org. http://www.mindfully.org/Industry/2005/Sullivan-WorldCom-Rat12aug05.htm

Jeff Clabaugh (2005). “WorldCom’s Betty Vinson Gets 5 Months in Jail.” Washington Business Journal. Retrieved from: http://www.bizjournals.com/washington/stories/2005/08/01/daily51.html

David Hancock (2002). “World-Class Scandal at WorldCom.” CBSNews.com. Retrieved from: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/world-class-scandal-at-worldcom

Fred Langan (2008). “The $50-billion BMIS Debacle: How a Ponzi Scheme Works.” CBCNews. Retrieved from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/the-50-billion-bmis-debacle-how-a-ponzi-scheme-works-1.709409

Susan Pullman (2003). “How Following Orders Can Harm Your Career.” The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: CFO.com. http://ww2.cfo.com/human-capital-careers/2003/10/how-following-orders-can-harm-your-career/

Amanda Ripley (2002). “The Night Detective.” Time. Retrieved from: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1003990,00.html

Scott Reeves (2005). “Lies, Damned Lies and Scott Sullivan.” Forbes.com. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/2005/02/17/cx_sr_0217ebbers.html and

Time Magazine (2009). “Top 10 Crooked CEO’s.” Time.com. Retrieved from: http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1903155_1903156_1903160,00.html