11. Qualitative Data Analysis

11.3. Writing Up Qualitative Results

Learning Objectives

- Describe the sandwich method of writing up qualitative data.

- Discuss the amount of descriptive detail you can and should include about your research participants to complement their quoted statements.

Now that you’ve analyzed your qualitative data, how do you write up your results? The bulk of your findings section will usually consist of quotations from your interviews or extended descriptions (excerpted in a more or less edited form) from your field notes. It should be organized by theme rather than just being a random list of quotes or observations. In fact, it is often a good idea to break the results section down into subsections, with each theme explicitly noted in its subsection title. Within each subsection, you can then describe overall patterns in the data related to that theme as well as specific cases that back up your interpretations of what you observed or what your interviewees said.

There are a wide variety of ways to write up the paragraphs in your paper that describe patterns and cases, but we’ll go over a staple approach, the so-called sandwich method.[1] Let’s say you want to use an interview quote to make a particular point in your paper. The quote—the qualitative data—will be the meat (or vegan meat substitute) for your sandwich, surrounded by two buns of analytical context. If you are analyzing ethnographic observational data, then you would swap out that interview-based patty with an observation-based one (such as quoting the relevant field note or summarizing your observations in one or more sentences).

The “sandwich” is typically the description of a single case (a single interviewee, observed episode, or so on). Let’s break down its layers:

- The top bun starts at the theoretical level. To begin the paragraph in your write-up, you make a theoretical point, such as indicating that a particular pattern exists in your data.

- Next, you move to the empirical level. The meat is the interview quotation or observational data you wish to include. Here, you introduce the example of a particular participant, episode, or quote to back up your theoretical point (or complicate it). You will usually want to provide a description of any participant you mention or quote. This might include their name or pseudonym, age, gender, race, and any other relevant background details so that your reader knows something about the social position of the person you’re referring to (more about this later). Either before or after that description goes the actual observational data, blockquote, or in-text quote or paraphrase.

- The bottom bun returns to the theoretical level. Here, you might want to reiterate your earlier theoretical point in different words, saying concretely how the example you just gave supports that point. You might provide some useful context for situating your example among the many episodes you observed or people you talked to. And you might discuss any exceptions or qualifications to your main point—for instance, explaining whether and why certain other cases deviated from the overall pattern). At some point, you will transition to the next case—perhaps to another “sandwich” entirely, or perhaps directly to the “meat” of a second example directly related to the first (for instance, an example that contradicts or complicates the point you just made). You can discuss the contrasts and comparisons you are making between cases here, or you can pivot to an entirely new topic, perhaps starting a new paragraph to do so.

It’s worth reiterating that the sandwich method is just one (formulaic) way of presenting the results of qualitative analysis, and many approaches are perfectly fine. For instance, sometimes ethnographers like to set the scene before making any theoretical points. They will have a paragraph or multiple paragraphs describing an episode or interaction—in other words, going right to the meat and skipping the top bun (the open-faced sandwich method, perhaps?). Then they will discuss that block of qualitative description in theoretical terms, indicating what broader point or points they believe it makes.

One particularly good strategy that fits well with the sandwich method is to juxtapose two cases—perhaps two respondents or two settings—that are similar in many regards, but different in one key aspect. You would use the sandwich method to describe the first case, and then pivot to the second. This case-to-case comparison is good for theorizing how any differences in outcomes between the two cases may be related to the specific factor you singled out. You can make a case for how one independent variable, for instance, may be decisive across these cases, or how the causal mechanisms at work differ across these two cases. You can even structure your write-up like a double-decker sandwich: the single bun between the meat of the two cases can flag the key difference between them, and the bottom bun can focus on explaining the significance of that difference.

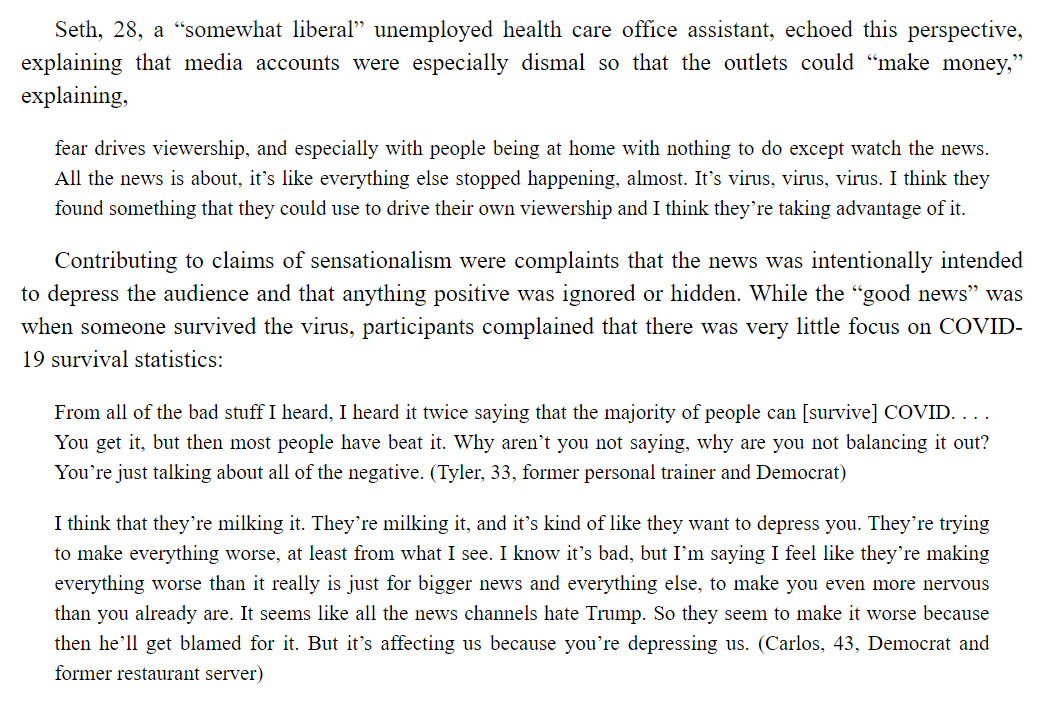

As we mentioned, the middle portion of the sandwich—your empirical data—can be in the form of a blockquote, an extended quotation that is indented (typically by a half-inch) to highlight it. In addition to interview quotes, blockquotes can feature excerpts from field notes, though it is usually more straightforward to include that observational material directly in the text rather than setting it off in this way. When you indent quoted material as a blockquote, you should not put quotation marks around it. The blockquote’s text should be single-spaced even if the rest of the text is double-spaced, and the text size can be set slightly smaller. Any parenthetical citation or attribution goes after the period or other punctuation that ends the blockquote, as shown in Figure 11.12, and it does not require its own concluding period.

Writing styles have different conventions about how long a piece of text needs to be before you should use a blockquote. For instance, APA and ASA style place quotations in a block when they are more than 40 words, while Chicago style has a 100-word threshold. However, you should use your judgment about when a blockquote is called for. A downside of blockquotes is that your theoretical point may get muddled when the excerpted text is too long. Too many blockquotes can also make your writing seem dull and formulaic. It may be better to use a mix of direct and indirect quotes and paraphrases to convey the same information.

What follows are some general pointers about how to write up qualitative data that apply to both interview and observational data:

- Use past or present tense consistently. Using either tense is fine when describing a scene or attributing a quote, but unless it is really necessary, try not to switch back and forth between tenses, which can be disorienting for the reader.

- Avoid using distracting attribution words in quotes. For the most part, you can use “said” (or “says”) and “replied” (or “replies”) exclusively. These words don’t draw as much attention to themselves, which means your readers will focus on the points you’re making rather than your flashy prose.

- Put the attribution after the quote. Unless you’re using a blockquote (discussed later), it generally sounds better to put the attribution after the quote (“I love sociology,” she said) rather than before it (She said, “I love sociology”). If you have a quote that is more than two sentences long, you can put the attribution between those two sentences (“I love sociology,” she said. “It’s so much sexier than economics.”). Of course, mixing up the format for attributions also works fine and can make your writing livelier. If you’re writing for a publication that uses American (as opposed to British) English, then make sure to put any punctuation within the quotation marks rather than outside it—with the exception of quotation marks and exclamation points that are actually part of the quote.

- Refer to “interviewees,” “respondents,” or “participants.” As we mentioned in Chapter 10: In-Depth Interviews, the term “interviewees” probably sounds the least awkward to lay readers, so you probably want to stick with that if you’re interested in making your work more accessible. With that goal in mind, we’d also suggest avoiding more stilted terms like “interlocutors” or “subjects.” The catch-all term “research participant” or just “participant” is fine to use when talking about someone you observed but did not interview.

One useful practice that ethnographers have adopted for writing up results is to reserve quotation marks only for interview data whose wording they are certain about—that was recorded and transcribed, for instance. When recounting quotations from memory or quickly jotted-down notes (sometimes the only options available when observing in the field), researchers will use italicized text to note that the quotation may not be a precise word-for-word transcription of what the person said.

Writing Up Interview Results

When you are writing up material from in-depth interviews, there are several additional issues to consider. First, you will have to find a way to introduce each interviewee and provide a few details about their background to put what they say in context. Here is what typically goes into that brief introductory description:

- Pseudonym. If you have promised confidentiality to your participants, which is typically the case, then you obviously can’t use their real names. That said, we’d suggest using a made-up name rather than just “Respondent A” or “Interviewee 17.” A made-up name is much more memorable for the reader than a generic label, and pseudonyms are especially useful for interviewees who are more important to your research and you plan on quoting multiple times. On the other hand, if you are quoting a respondent only once, it’s also acceptable to leave out a label altogether (for instance, by simply describing the person as a “a 20-year-old African American female student” and including their quote).

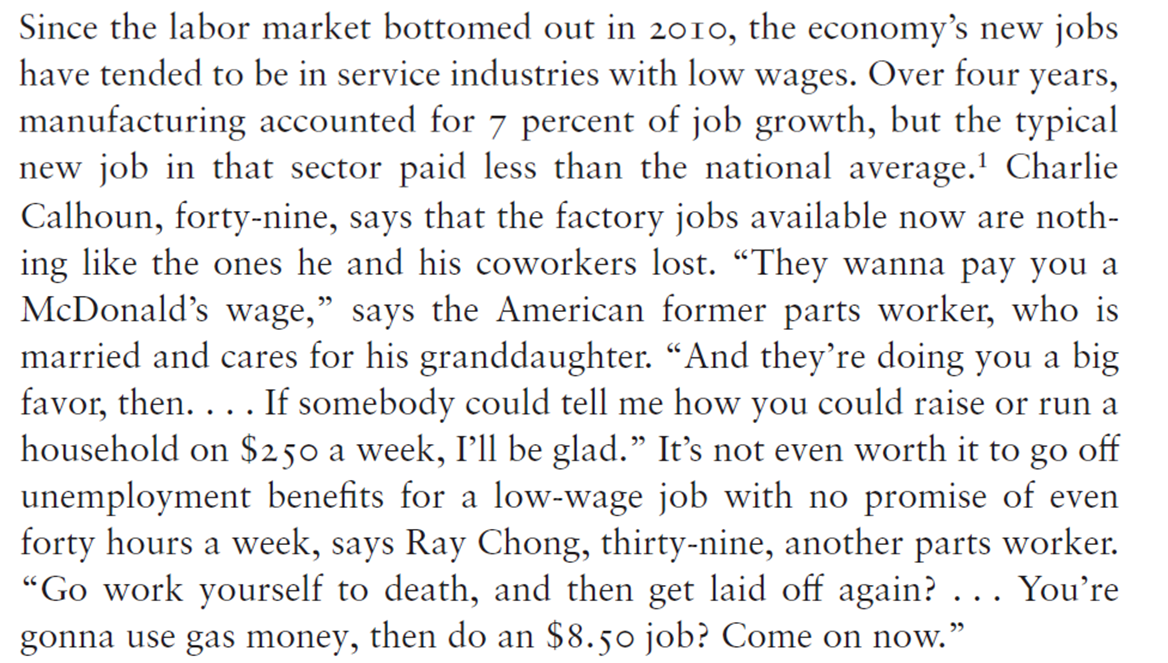

- Background details. Generally speaking, it is a good idea to include some background about an interviewee when you introduce them in your paper, so that the reader knows something about their social position in relation to other respondents (and therefore how to put their words in context). Age, gender, and race are fairly standard to include, given their importance as social markers in our society—for example, “Samantha, a 32-year-old Latina woman from Richmond …” Other details like the respondent’s occupation or position within an organization, their socioeconomic status (education level, self-identified social class, or even income level), and their city of residence are also common. That said, you should include whatever descriptors are most relevant to your study. For instance, if you are doing a study that examines the attitudes of various sexual minorities, you might want to mention the sexual orientation of each respondent. Note that you do not have to include all of these details in a single sentence, which can make your writing clunky. As shown in Figure 11.13, you can instead spread out relevant details across the sentences of a paragraph. For blockquotes, you may want to put the identifiers in parentheses at the end of the quotation, especially if you have blockquotes from different respondents that you need to distinguish. For instance, “(Respondent A, 23 years old, working-class African American male student)” would appear at the very end of that individual’s quote, even if the blockquote was multiple paragraphs long.

How should you write up your interviewee’s actual words? Again, there is no “right” way, but we would advise that you use full quotations—whether blockquotes or not—only when you have an especially expressive, eloquent, or theoretically compelling quote that you want to highlight, or when it is important that you present a longer quote to provide context. Partial quoting (of a few words or phrases) or paraphrasing is appropriate for conveying more straightforward information, and this approach will ensure that your voice and your theoretical arguments are not lost amid your respondents’ words. Save up the direct quotes for powerful and provocative material.

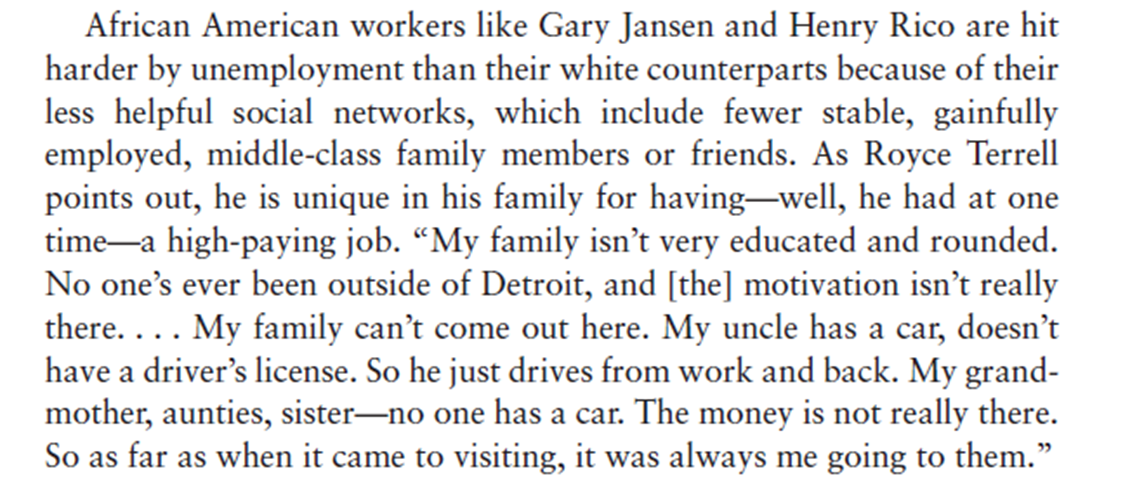

On a related note, including lots of interviewees in your write-up can clutter up your analysis, especially if they are saying more or less the same things. While it can be important to convince readers that you have not cherry-picked your respondents and actually did talk to a wide range of people, you don’t want your paper to become a wall of quotes from faceless people. Prioritizing key cases and vivid quotes will play to the strengths of qualitative research and allow your theoretical points to come across clearly and indelibly. In fact, some qualitative researchers will choose in their articles or books to showcase a very small group of exemplary cases—say, three to six interviewees. The analysis will return again and again to the stories of these focal participants or key informants, as if they were the main characters in a play. Like bit players, other respondents will appear only occasionally, their data occasionally sprinkled in to complement a particular point being made. This focused approach to writing up qualitative data (used almost exclusively in trade books meant for popular audiences) can help ground the narrative and make it much more accessible to readers.

When quoting people, it is generally acceptable to make slight edits to their wording in order to more clearly convey what they meant to say. So long as you are not altering their intended meaning, for instance, you can fix minor grammatical errors or add any words that they inadvertently left out. In these cases, you normally want to put the inserted text in brackets and indicate any cut text with an ellipsis. You can see an example in Figure 11.14. Note that writers sometimes use an ellipsis enclosed in brackets to signal that text was removed (as opposed to the respondent pausing in their speaking). This added step is not strictly necessary, however, and it will make your writing seem more technical. You also don’t need to use brackets or ellipses when you remove so-called filler words, meaningless phrases that people naturally insert into their speaking as they think through a response: “um,” “like,” “you know,” “ah,” “hmm,” “right,” and “alright,” for instance. That said, you may want to leave a few filler words in your quotes, which can make the language livelier and also offer subtle clues about what the person was thinking or feeling when they said what they said.

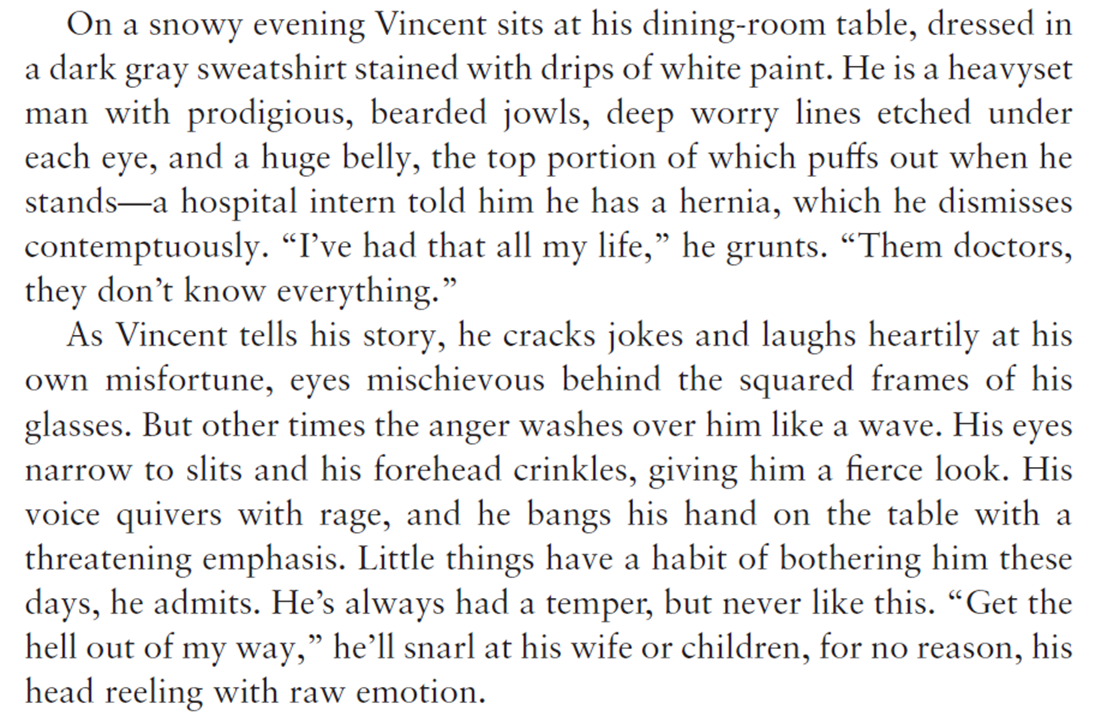

We’ll wrap up this discussion of presenting interview data with some additional thoughts on providing background details about your respondents. Victor—who, as previously noted, was originally trained as a journalist—likes to provide additional information about each interviewee, including describing their physical appearance, to flesh out their individual portrait in a published text. You can see what this looks like in Figure 11.15. With your institutional review board’s stipulations in mind, you will need to decide on what you find appropriate in terms of the level of detail and context you provide. You obviously need to honor any promises of confidentiality you gave to your respondents, and including too much information may risk violating that confidentiality. Furthermore, providing details like physical appearance can come across as unflattering or even creepy. Ethnographers sometimes regret even an offhand, seemingly innocuous comment that, they later learn, a research participant felt slighted by (Lareau 2011).

Many interview-based studies rely wholly on the words of their respondents as data, not using any observational information, and that is perfectly fine. If you were doing interviews for a program evaluation, you probably wouldn’t even want to gather nonverbal detail: you just want their opinions about the program, and it would be awkward to include more. That said, as we discussed in Chapter 10: In-Depth Interviewing, observational data can add depth to the spoken interview data, providing vital clues about a respondent’s social position and their attitude or orientation toward the things they say. If we focus just on the words alone, we may miss valuable signals about how people hedge their answers, convey passion about a particular topic, feel ambivalent or apathetic about the particular line they’re giving the interviewer, or harbor internal contradictions and tensions that they may not express in their language (Pugh 2013). Likewise, visual descriptions of people’s appearance and their surroundings can situate the reader in their social realities to the point that they do not come across merely as disembodied voices saying words. For instance, clothing can tell us something about their socioeconomic status, while expressions of exhaustion and disgust can convey the underlying moods that color their responses to particular questions. All this additional information helps us with triangulation, introducing complementary and potentially confirmatory data that allows us to vet and expand upon what we learn through people’s spoken statements.

Ultimately, good qualitative work is storytelling, and one way you make your qualitative cases vivid, memorable, and theoretically rich is through detailed narrative and description. Sometimes respondents appreciate this immersive approach, which helps them feel fully heard and seen in the published text. And even if you don’t wind up using all the details you gather, it can just be good practice to record in your field notes as much information as possible—verbal, visual, and otherwise—so that you know you are making full use of the qualitative method, which is unique in allowing for this flexibility.

Key Takeaways

- The sandwich method takes a specific empirical case (or group of cases) and contextualizes it theoretically. It starts by presenting an overall pattern or argument, providing empirical support for that point, and then either reiterating or building upon that point, often in reference to other cases.

- When writing up interview data, you should provide context about your respondents by including demographic and other pertinent details whenever possible. If appropriate, you may also wish to complement their quotes with descriptions of their appearance, mannerisms, and actions, which can provide clues about their social position, their current state of mind, and other useful background information.

- Victor thanks Katherine K. Chen for alerting him to this method and its name. ↵