9. Ethnography

9.3. Field Jottings and Field Notes

Learning Objectives

- Describe the various ways that ethnographers take notes while in the field.

- Discuss what information is important to collect when taking field notes.

When ethnographers are observing in the field, they typically write off-the-cuff, descriptive notes about what they saw and heard. These are called field jottings. Then, when they leave the field, they take these jottings and put together a memo of their observations for that particular time period, which is known as a field note. Let’s go over each type of note-taking, both of which are essential to the ethnographic process.

Field Jottings: Writing in the Field

As an ethnographer, there isn’t one right way to write field jottings. If you can conduct your fieldwork in a setting where sitting with a notebook, tablet, or computer is no problem—such as when you are observing a classroom or meeting—then recording your observations at length and in detail will be pretty straightforward. If you are in a location where taking notes would be rude or make people uncomfortable, however, you have to weigh the benefits of extensive note-taking against the dangers of sticking out. Covert researchers will obviously not want to be seen taking notes, which may prompt questions that blow their cover. Yet even overt researchers should be concerned about how people will act differently when they are aware that someone is writing down everything they do or say. A lack of discretion can open up the possibility of social desirability bias or other reactivity problems of the sort that we described earlier.

Your strategy for recording your observations while in the field will be determined mostly by the site you choose and the role you decide to play in that site. Will you be in a setting where having a notebook or smartphone in your hands will look out of place? If not, by all means, take extensive notes! But don’t let your note-taking distract you from what’s happening around you. At times, you should just take in the scene. If you are a participant in addition to an observer, you may also want or need to focus on engaging with the setting and the people within it. In fact, participant observers often find that they have their hands too full to write any notes at all (more about that later).

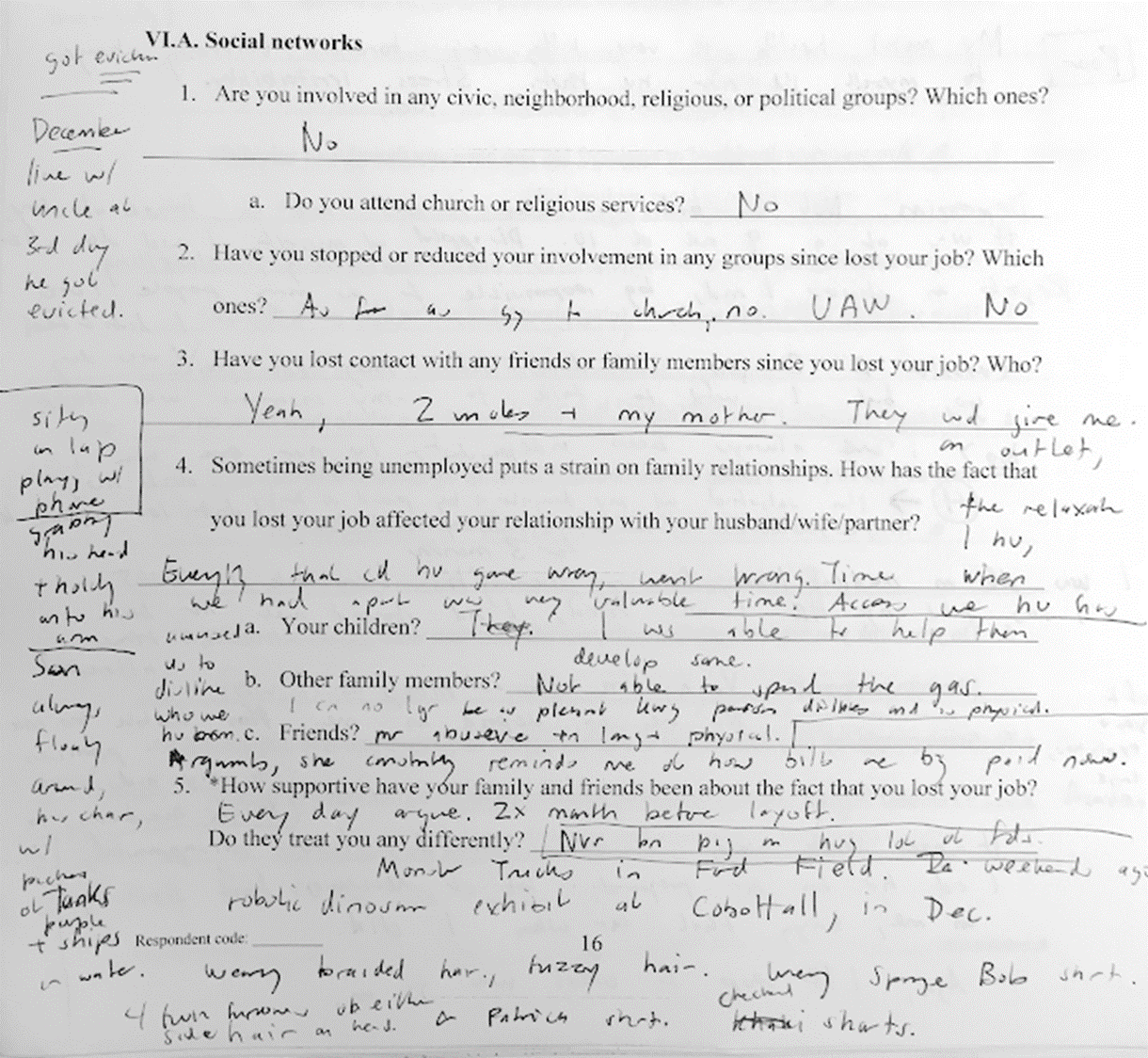

In cases where copious note-taking isn’t possible or desirable, you can record your observations in more casual ways. For instance, the fact that smartphones are so common nowadays means that ethnographers can unobtrusively write down their observations in a notes app or email while appearing, like everyone else, to be texting or surfing the web. Other strategies can include keeping a tiny notebook in your pocket and whipping it out whenever you need to jot something down, dictating quick observations into your phone’s voice memo app or a recorder, or—if you really want to go full-on Cold War spy—writing key phrases on your hands and arms or scribbling notes on toilet paper during visits to the restroom. With these more surreptitious approaches to note-taking, you’ll need to develop a way of jotting down observations that doesn’t require complete sentences or perhaps even words. Sometimes, ethnographers develop their own version of shorthand to take notes, using some combination of abbreviations and symbols. Other times, they will take pictures or videos of what is going on around them, which they can refer to later to jog their memories of what they observed. (Be aware of your IRB’s stance toward the collection of such supplementary data, however.)

At the jottings stage, the notes you write will be descriptive. That is, you will want to describe what you saw or heard (and, if applicable, smelled, tasted, and touched) as clearly and deeply as possible. Draw pictures or diagrams if it’s helpful. You might also want to make note of some initial personal impressions or reactions (more about this later), though generally speaking, you will want to provide a straightforward, factual account. Remember that your ultimate goal is thick description, a detail-rich account of what you observed that connects people’s actions and words to their specific context. While the cultural interpretations and layered social meanings of your observation won’t necessarily be clear at this stage, by writing up a vivid description you will be in a good position later on to engage in that sort of analysis.

Here are some questions you might ask yourself in the field, adapted from a helpful list developed by Vanderbilt University’s Writing Studio (2012):

Space:

- What is the layout of the space or room?

- What are the specific objects or physical elements in the space?

- Do these features of the space affect the interactions taking place in any way? Do they communicate anything about the people frequently in this space?

People:

- Who are the people involved? (Single out specific individuals and interactions to describe, in addition to providing an overall sense of the composition and tendencies of the group or groups.)

- What are people wearing? What does it say about who they are, or how they are feeling in the moment?

- What clues signify people’s statuses and roles? Are there aspects of their appearance or demeanor that signal how they relate to other people in this space?

Actions and motivations:

- What are the people you are observing doing in general or attempting to accomplish?

- What are individuals’ specific behaviors—both verbal and nonverbal?

- How do people interact with one another? How do they interact with their surroundings? (Single out specific interactions to describe, in addition to providing an overall sense of how the group or groups interact.)

Emotions:

- What is the affect of the people you are observing? What emotion (or noticeable lack of emotion) are they expressing? How are they expressing it?

- What clues are there about people’s feelings about one another or the nature of their relationships?

Rules and norms:

- What structures, rules, or norms govern the situation? How explicit or implicit are they?

- How are expectations conveyed? Are there individuals who are policing these rules or norms? Are there posted signs or other nonverbal ways of communicating what is expected?

Writing useful field jottings is a skill that you will need to master. The observation involved here is deliberate, not haphazard—though it may seem haphazard to a novice researcher. With practice, you’ll get a better sense of when to write, what to write, where to write, and how to write. For instance, try observing a setting in your neighborhood, school, or workplace for just 15 minutes. How hard can it be? Pretty tough, if you do it right. There is always too much detail to write down—everything from how people dress, to what the weather is like that day, to how the space is laid out, to what expressions and tone of the voice people use while interacting. This becomes all the more apparent if you compare your notes with those of other people who observed the exact same setting. (In Exercise 1 at the end of this section, we’ll run a little experiment along these lines.) There may be overlap in the things each of you note, but inevitably one person will have paid more attention to conversations overheard, another person to people’s actions and mannerisms, and yet another to the nonhuman dimension—the surrounding landscape, the ambient sounds and scents, and so on. You and your fellow observers will probably use different note-taking strategies, too: some might write complete sentences, while others might have abbreviations, idiosyncratic personal symbols, or drawings in their notes.

In conducting this sort of exercise, you’re likely to experience not just how difficult the task of observation can be, but also how arbitrary and aimless it can feel. Having a research question or topic in mind helps a researcher focus their observations, and that is one lesson to learn: come into the field with some plan about what you want to observe, so that you aren’t overwhelmed by the sheer amounts of data. That said, part of the point of ethnography’s inductive approach is to make sense of the seemingly chaotic interactions and activities witnessed in the field. In that sense, the ethnographer needs to be comfortable with a certain degree of ambiguity, and with making their own decisions about what aspects of the vast array of phenomena they observe is worth jotting down. As usual, there is not often a right or best answer. Furthermore, it is important that ethnographers not allow their original question or topic blind them to other occurrences in the field. When conducting observations, you want to write down as much as you can, because oftentimes something that may seem unimportant at the time ends up being important down the line—sometimes only years later, when you’re writing up your work for publication. As we’ve emphasized, one of the strengths of ethnography is its ability to generate new theories, rather than just refining or testing existing ones, and that creativity depends on observing the unexpected.

No matter how difficult it can be to write jottings while in the field, it is worth the effort. Ethnographers rely on them to develop more complete field notes later on. Even if you have to be extremely cautious or spare in your note-taking, try to jot down a few things very quickly while you’re in the field. Something is better than nothing. You may have the temptation to skip the jottings stage and just write down what you remember in a field note, but this is a risky strategy. Your memory will quickly fade once you leave the field, and the amount of detail you can recall just hours later will be much less than what you can reconstruct from jottings. Furthermore, research finds that eyewitness accounts actually become distorted with time, as people unconsciously revise the memories in their minds based on what is most familiar or expected.

As we pointed out earlier, sometimes writing jottings in the field is utterly not an option—in which case you will want to write down everything right after your observation. But in general, both field jottings and field notes (the more formal note-taking we’ll describe in the next section) are critical. Together, they allow the researcher to generate the thick description that allows for insightful analysis.

Field Notes: Processing What You Observed

The next stage in the ethnographic process can begin as soon as you end your current observation session, your messy jottings or recordings in hand (in some cases, literally on hand), At some point, you’ll want to sit at a computer to type up those notes into a more readable format. That said, we recommend that you take some time to review and possibly flesh out your field jottings immediately upon leaving any observation in the field, even if you can’t turn them into a formal field note just yet.

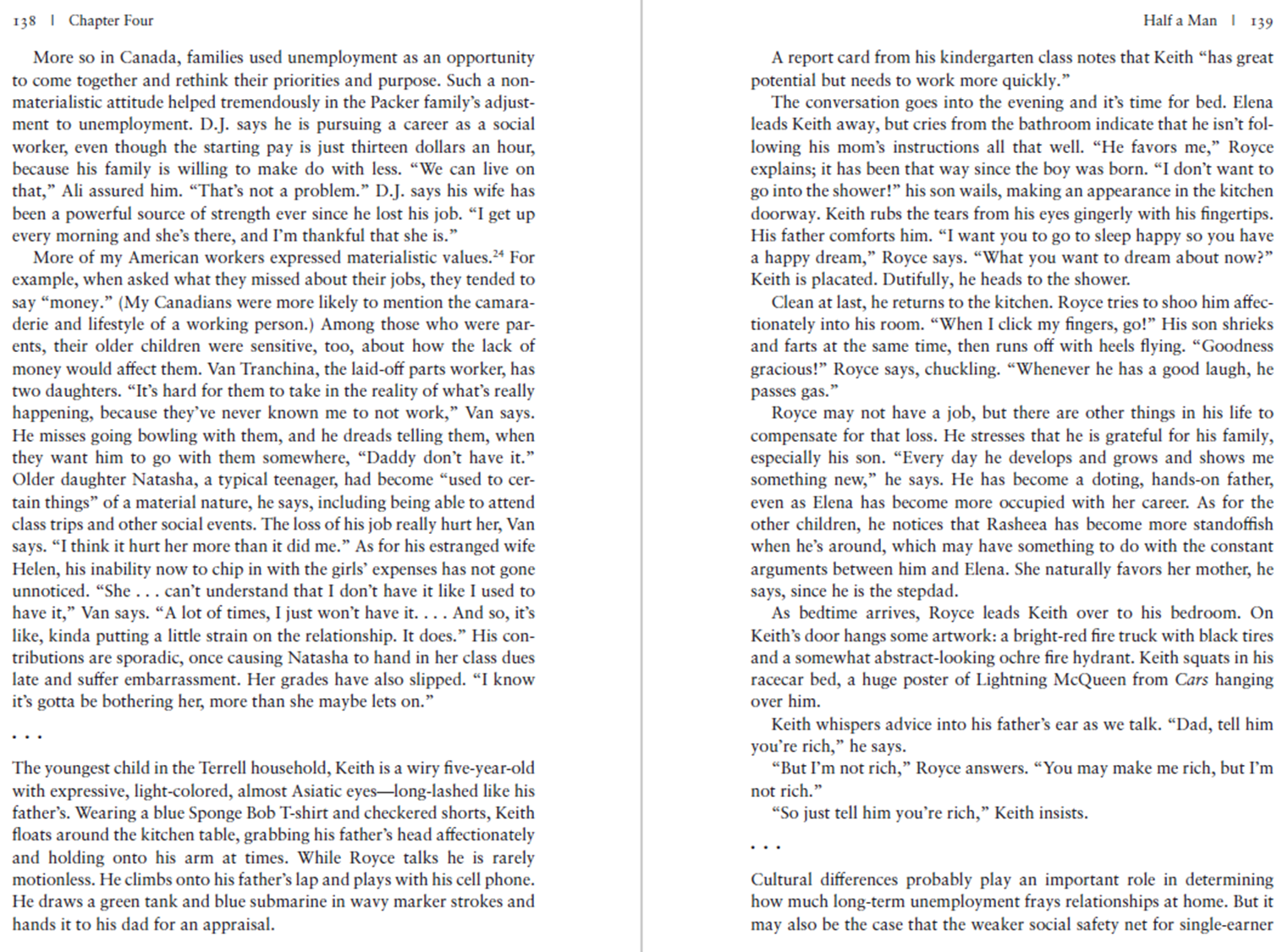

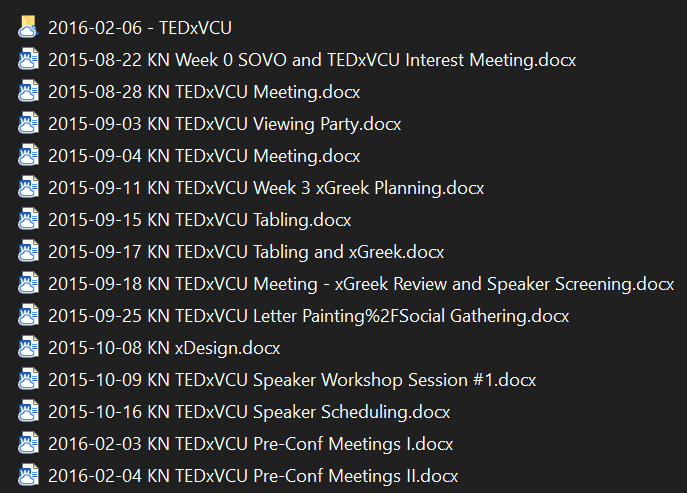

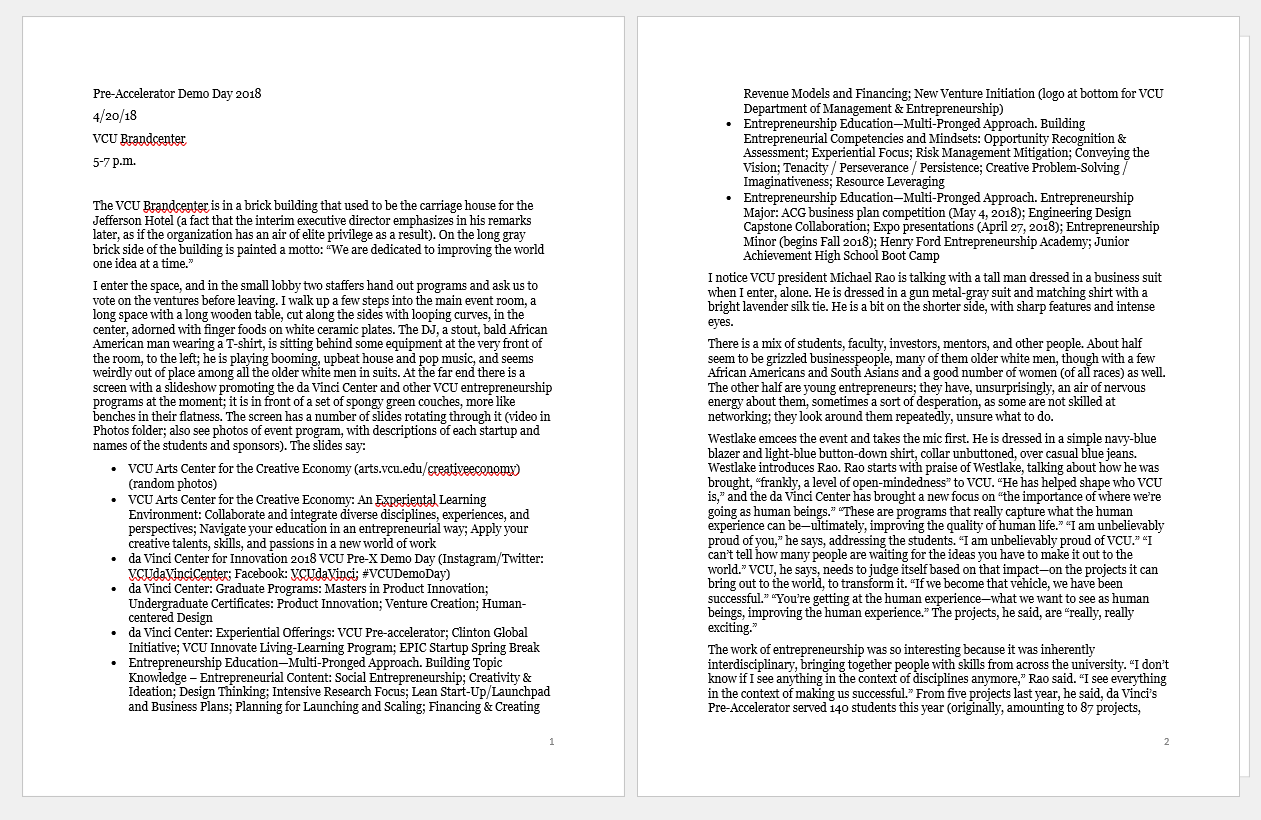

When you finally start writing your field note, you will typically want to create a new document in your word processor devoted to that single observation session. One alternative is to write your field notes as dated entries in a single document, but we’d suggest having each field note be its own document to make your life easier later on. As shown in Figure 9.4, this approach allows you to order your field notes by date and store them in folders representing different types of observations (for instance, what organization, site, or event the observation focused on). As you’ll see in Chapter 11: Qualitative Data Analysis, storing your field notes in separate files also works well with the qualitative data analysis software packages you might use during the coding process, which naturally treat each document as a separate observation.

As you write up your field note, don’t worry so much about the quality of your prose. Sometimes ethnographers quote directly from their field notes in their published work, but that is not required, and we’d suggest not overthinking these memos: just write whatever comes to mind, as soon afterward as you can. The goal is to record your observations as straightforwardly and quickly as possible in a way that makes sense to you. Even if you felt that the descriptions you recorded in the field were more or less complete, you’ll be surprised by how much more you’re able to recall once you sit down without distractions and read through what you’ve jotted down. You’ll also have the opportunity to add your own reflections—your observations about your observations—when you reach this stage in the research process.

In your field note, fill in the blanks of your jottings, writing down as much as possible about what you’ve observed. Even if the details seem microscopic or mundane, they may come in handy later. (Minute details may also make your narratives a richer and more compelling read, helping your sociological work reach a broader audience.) Indeed, some say field notes can never contain too much detail—though you also want to be kind to yourself as a researcher and not make every brief episode of observation into such an arduous note-taking task that you are discouraged from keeping up with your observations (remember, ethnography is a marathon, not a sprint).

Ethnographers typically spend several hours typing up field notes after each observation has occurred. A good rule of thumb is that every hour of observation requires at least two hours writing up field notes. You should pace yourself and figure out what note-writing approach works best for you. For example, for his ethnography of drug robbers in the South Bronx, Randol Contreras began his project writing up meticulous field notes about his interactions and observations. After three months, however, he started putting a tape recorder in his jacket or pants pocket and bringing it everywhere he went. “The tape recorder improved my recollection of events since I often got back home in the early morning, usually intoxicated from heavy drinking,” Contreras writes (2012:13). “Nevertheless, I wrote up extensive outlines before going to bed (which sometimes took over two hours) and then wrote elaborate field notes the next day. These notes supplemented and guided the tape recordings, especially since street sounds sometimes interfered with the sound quality, and sometimes weeks passed before I found time for transcription.”

Writing as much as possible, in as much detail as possible, should also help you avoid generalizing in your field notes. As in good fiction writing, the mantra here is “show, don’t tell.” Be specific about what you observe. You won’t end up using all or even most of the details you’re writing down, but when you get to the analysis and writing stages of your research, you want as much material as possible. It will help trigger ideas for nuanced and well-grounded theories, and it will allow you to immerse the reader in the social contexts you observed.

As illustrated in Table 9.2, avoid any vague descriptions and generic adjectives in your write-up. Rather than saying that someone you observed was “angry,” describe what gave you that impression—was that person yelling, red in the face, shaking their fist? Rather than describing people as “nice” and “fashionable” or a setting as “fancy,” say what exactly a child did to appear “nice,” what specific items of clothing a woman wore that made her seem “fashionable,” and what kinds of decor, lighting, music, and even table settings made a restaurant seem “fancy.” Rather than saying that “everyone” said or did something, make note of exactly who said or did X (or note that you’re not sure exactly who did so, but that it seemed as if most everyone did).

Use similes and analogies to help make your characterizations more concrete and visceral—for instance, describing a “large” room as the size of a football field, or comparing an adult’s “violent” outburst to a red-faced toddler’s tantrum. Capture specific interactions you observed—noting how you participated, if you did. And summarize conversations you overheard, providing direct quotes whenever possible. Even a few words of remembered dialogue can say so much more than a blanket description of how a person expressed disapproval or happiness.

Table 9.2. “Telling” vs. “Showing”

|

Telling |

Showing |

|

“I’m sorry,” she said, clearly upset. |

“I’m sorry,” she said, looking down at the ground with slumped shoulders. |

|

He was dressed sloppily. |

He wore a red Henley shirt over faded light-blue jeans with a hole ripped into the right knee. His shirt was untucked and none of the three buttons were buttoned. |

|

The protesters seemed aimless and confused. |

The protesters wandered through the hallways, popping their heads into open doorways. Those at the front of the crowd seemed to lack any direction or plan, moving hesitantly through the building like the blind leading the blind. |

|

“We love you!” the crowd shouted, cheering her on. |

“We love you!” shouted a middle-aged man from the upper balcony, and the rest of the crowd started whooping as the singer picked up the microphone. |

Don’t forget to describe exactly where you were and detail your surroundings. Physical descriptions of the people you observe can also be helpful, though in all of this data collection, be conscious about your IRB’s strictures regarding confidentiality. When describing people or objects physically, one trick is to go from top to bottom (or left to right) making note of every detail you see along the way. This has the added benefit of focusing your attention on what you can concretely show (“he had droopy eyelids”) rather than vaguely tell (“he was tired”).

Early in an ethnographic study you will probably focus more on describing your surroundings, the appearance of the people you encounter, and other introductory details than you do later on, when the focus will be primarily on how people interact or what events transpire. This means that your initial field notes will include very detailed descriptions of the locations you observe and the people with whom you interact; you might also draw a map, or—if appropriate in your setting—take pictures or videos of your field sites. It is crucial to have documentation early on of your first impressions, and with time, these sorts of details may become so much a part of the everyday scene that you stop noticing them. If your observations are being conducted in the same places and with the same people, you won’t need to write up the same descriptions in later field notes; instead, you can focus on the interactions and events you observe, updating your initial descriptions of individuals or surroundings only as they change in relevant ways.

Figure 9.5 offers an example of a field note from Victor’s research. One thing you’ll notice is that Victor used quotation marks every time a person was directly quoted. He also paraphrased people’s words without quotes (with an attribution like “said”) when he wasn’t confident he captured the exact quote. In your own field notes, include as many quotes as you can. In particular, direct quotes can provide important support for the analytic points you’ll make when you later describe patterns in your data. This is another reason that taking notes in the field is a good idea: direct quotes may be impossible to remember hours or even minutes after hearing them. (For this reason you may also wish to focus in your field jottings on writing out any pertinent verbatim quotes and then only later take the time to describe the circumstances under which something was said when you write up your field notes.) That said, partial quotes or paraphrases are fine if you can’t catch people’s precise wording. Again, you are never going to capture everything, so do your best, pace yourself, and don’t beat yourself up if you miss something you think is important—there will be more opportunities to follow up.

Another thing you can see in the example field note in Figure 9.5 is that researchers will record their own feelings and impressions in their field notes. The personal reflections in your field notes may never be used, but in some cases they will serve as a preliminary analysis of your data. At times, researchers will also use their field notes as a constructive opportunity to “vent”—express emotion or purge difficult thoughts or feelings that arise when they become upset about or annoyed by something that occurred in the field. As we’ve noted, ethnography requires developing personal relationships with participants, and any interpersonal relationship can become fraught or volatile. Feel free to express your feelings in your notes. These details may become important for analysis later, but even if not, writing them down can be cathartic. They might also reveal biases you have about the participants that you should confront and be honest about.

Every researcher’s approach to writing up field notes will vary according to whatever strategy works best for that individual. For example, some ethnographers will distinguish between statements in their notes that are purely descriptive and those that are personal reflections or preliminary analyses. They may segregate the two kinds of content in separate sections of a field note. They may create two columns—one containing notes only about what was observed directly, and the other containing reactions and impressions. Or they may flag the latter commentary in special ways—adding brackets around the text, putting it in a different font or color, or embedding it in footnotes or comments. You don’t need to do all of this, however, and you should do whatever works best for you personally. What’s important is that you adopt a strategy that enables you to write accurately, record as much detail as possible, and distinguish observations from reflections.

Oftentimes, the tenor of your field notes will change as you conduct more observations. You may find yourself shifting from doing a lot of describing to doing much more explaining in your write-ups. In fact, some ethnographers say that there are two different kinds of field notes: descriptive and analytic. Descriptive field notes are notes that simply describe a researcher’s observations as straightforwardly as possible; analytic field notes attempt to explain or comment on those observations. Of course, line between what counts as “description” and what counts as “analysis” can get pretty fuzzy, and you may prefer not to compartmentalize your thinking in this way, but just let your field notes naturally take a more explanatory turn over time. Even so, one technique you might consider is to append an explicitly analytic field note to the end of the earlier, more descriptive one written immediately following your observations. This gives you the option at any later point to go back to that initial write-up and expound on your initial impressions and whatever thoughts have come to you since then.

With all the time you spend writing up field notes, you may be wondering why you aren’t just writing your paper manuscript at this point—why the extra step between field jottings and analysis? Field notes are the foundation of a quality analysis. As we said, you will find that you will be able to remember much more when you sit down to write up your jottings in a formal memo. Furthermore, you will start drawing interesting connections and thinking through how exactly the relevant social context of what you observed matters in terms of what people did or said. Once you move to the formal analysis stage, which we describe in Chapter 11: Qualitative Data Analysis, you will be able to draw from all these memos—which will number dozens or hundreds of documents at this point—and see the patterns across your observations from a higher-level vantage point. (In fact, as we’ll discuss in that later chapter, you can even import your field notes into a computer program, treating them as separate sources of data that you can easily categorize and compare.) All these stages of ethnographic research contribute significantly to the insightfulness and rigor of the work you ultimately produce. Finally, it’s worth noting that your field notes are the hard evidence and formal record of what you observed. If another researcher wanted to vet your ethnography, they’d look to your field notes to get a sense of your data and how you drew the conclusions you did. In fact, many ethnographers count their field notes or even tally up all the pages of written text in order to show that they did their due diligence in the field—for instance, saying something like their observations generated “100 pages” of field notes. (Alternatively, they will talk about how many events they observed, how many hours they spent in the field, and so on.) While we think it is generally a bad idea to fixate on quantifying your qualitative fieldwork—remember, depth rather than breadth is the key advantage of ethnography—you will want to keep some sort of accounting of the scale of your observations in case other scholars want more in the way of proof regarding the rigor of your ethnography.

Key Takeaways

- When taking notes in the field, try to record your observations as clearly and deeply as possible. It may be necessary to find unobtrusive ways of taking notes in the field, such as typing out notes on your smartphone.

- Note-taking does not end when a researcher exits the field. Try to type up your jottings as extended field notes immediately upon leaving the field so that you can expand upon what you observed (and what you personally felt in reaction to those observations) before your memory fades. Whenever possible, including analytic sections in your field notes that provide a preliminary analysis of puzzling occurrences or interesting patterns, which can help influence your next round of observations in the field.

- While observing, capture as much information as possible using all your senses. Describe individuals, surroundings, and interactions. Single out specific examples in addition to noting larger patterns. Details that may seem unimportant in the moment may turn out to be important during later analysis.

- Remember to show, not tell, when describing scenes or individuals. This generates rich detail that provides a firmer foundation for theorizing—in addition to helping you immerse readers in the social world you observed.

Exercises

- Recruit a friend or two to accompany you to a public space—perhaps a library, cafeteria, coffeeshop, or park. Each of you should observe the space and the people within it for about 15 minutes., writing notes to capture as many details as you can. It’s best to sit or stand near your friends, but do not talk with them so that you don’t influence what the other person writes. When your 15 minutes are up, compare notes. Where are there similarities? Where are their differences? Why do those similarities and differences exist? What strategy did you each employ to take notes? How might you approach note-taking differently the next time you do it?

- Let’s simulate an ethnographic observation of a much more chaotic scene. While watching Video 9.3 below, write field jottings. (Write them by hand to simulate conditions in the actual field.) The video has some longer segments, but it is edited, which means you may find it hard to follow—don’t worry about missing things. Try your best to capture as many details as you can. Then write up a page-long field note describing what you saw or heard. (In Chapter 11: Qualitative Data Analysis, we will analyze the data you collected, so hold on to your field note!)

Video 9.3. January 6, 2021. New Yorker reporter Luke Mogelson was observing supporters of U.S. president Donald Trump as they protested outside the U.S. Capitol, challenging the results of the 2020 election. When some protesters smashed windows and forced their way into the building’s entrances, Mogelson tagged along, using his phone to capture this footage of their actions within the building, including inside the U.S. Senate Chamber. You can use this video to practice ethnographic observation, as discussed in Exercise 2.