4. Research Questions

4.3. Posing Explanatory Research Questions

Learning Objectives

- Describe some common ways that sociologists pose explanatory research questions for qualitative and quantitative projects.

- Distinguish inductive and deductive approaches to empirical research, and provide examples of each.

- Understand how induction and deduction complement each other.

As we mentioned, explanatory research focuses on causal relationships—whether and how a change in one variable causes a change in another variable. As a result, explanatory research questions should contain an independent variable and dependent variable. The point of explanatory research is to determine the relationship between these variables (which, technically, are really concepts at this stage before we have specified how we will measure them—at which point they become variables). Indeed, as we noted before, when you are mulling over the concept map you created earlier in the chapter, you can devise a simple research question by singling out two boxes—two variables—listed on your map. An explanatory question could involve the relationship between any two of your boxes, which would be captured by the direction of the arrow connecting them—that is, the direction of the causal relationship that you believe exists between those variables. (For more context, refer to our discussion of causality in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research.)

Broadly speaking, the way that we pose an explanatory research question will be different when we are conducting a qualitative study and a quantitative study. One common format for an explanatory quantitative research question is this:

What is the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable within the target population?

A common format for an explanatory qualitative research question is this:

How (or why) does the independent variable affect the dependent variable within the target population?

We should point out that plenty of quantitative and qualitative studies phrase their research questions in different ways than what we’ve just suggested. However, we advise novice researchers to use these templates for a couple of reasons. First, as we described in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research, quantitative research tends to be better at assessing whether a causal relationship exists between two variables within the target population—and if the relationship does exist, it can quantify the strength of that relationship (i.e., the extent to which one variable affects another). Qualitative research, on the other hand, excels at identifying and describing causal mechanisms—the specific pathways or processes by which one variable affects another—and, in doing so, it gets at the how and why questions of that causal relationship. Posing explanatory research questions in these two ways therefore plays to the strength of each methodological approach: the ability of qualitative methods to generate complex data and nuanced explanations, and the ability of quantitative methods to isolate key variables, assess whether a cause-effect relationship between them exists, and estimate the size of that effect (if any) within the target population.

Furthermore, these two templates for research questions correspond—again, generally speaking—to the two major analytical approaches that sociologists take when conducting research: deduction (which is often the approach of quantitative studies) and induction (which is associated more with qualitative studies). When researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a set of observations and then move from those particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about how the world operates. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Researchers taking a deductive approach take the steps just described and reverse their order. They start with a social theory that they find noteworthy and then test its implications with data. In this way, they move from a more general level to a more specific one.

In deductive research, sociologists are usually building explicitly upon what others have done—reading existing theories of whatever phenomenon they are studying, and then testing hypotheses that come to mind when they apply those theories to specific social contexts. In inductive research, by contrast, sociologists are frequently generating new and original theories based on whatever patterns or regularities they’ve observed in social life, regardless of what past work has found (though, as we discuss later, most sociologists usually start their inductive investigations with some existing theories to expand upon or contest). Put simply, inductive research is focused on theory building, and deductive research is focused on theory testing. Both approaches are critical for the advancement of science. Elegant theories are not valuable if they do not match with reality. Likewise, mountains of data are useless until they can contribute to the construction of meaningful theories.

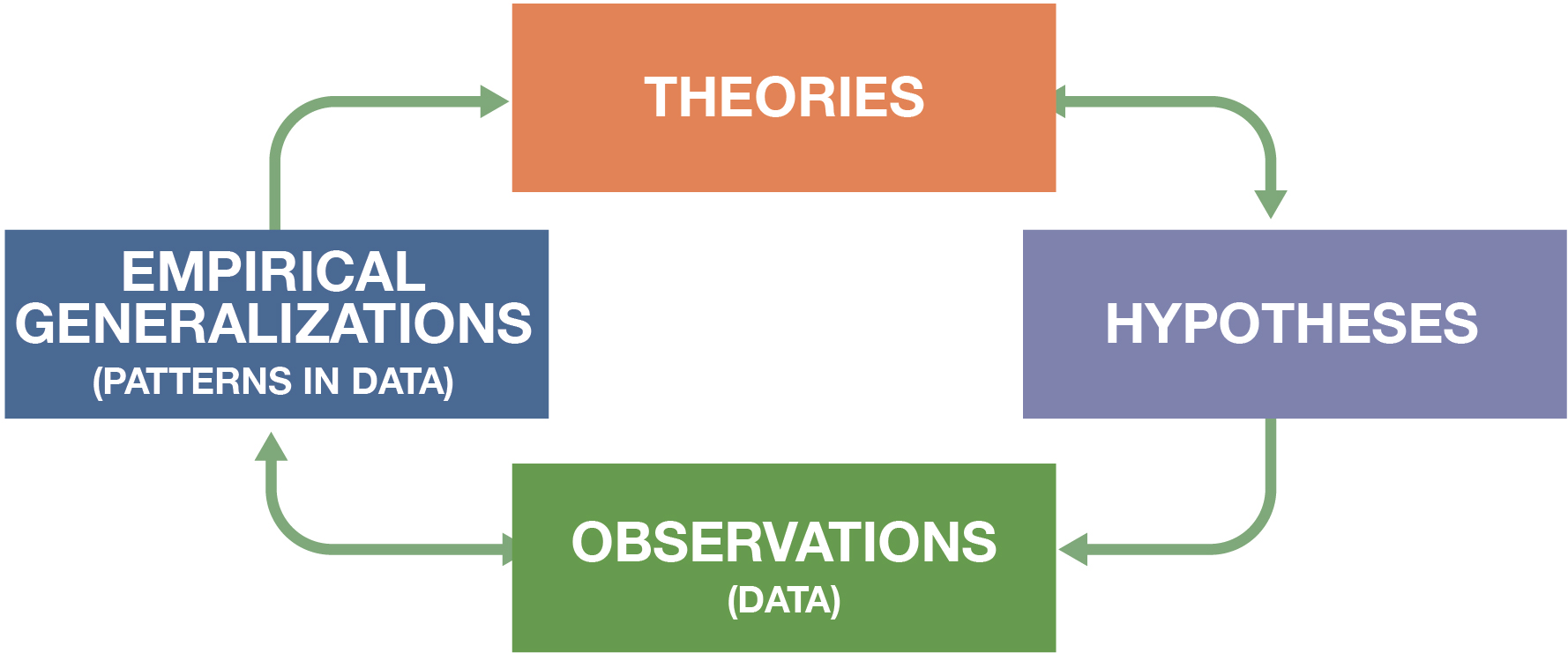

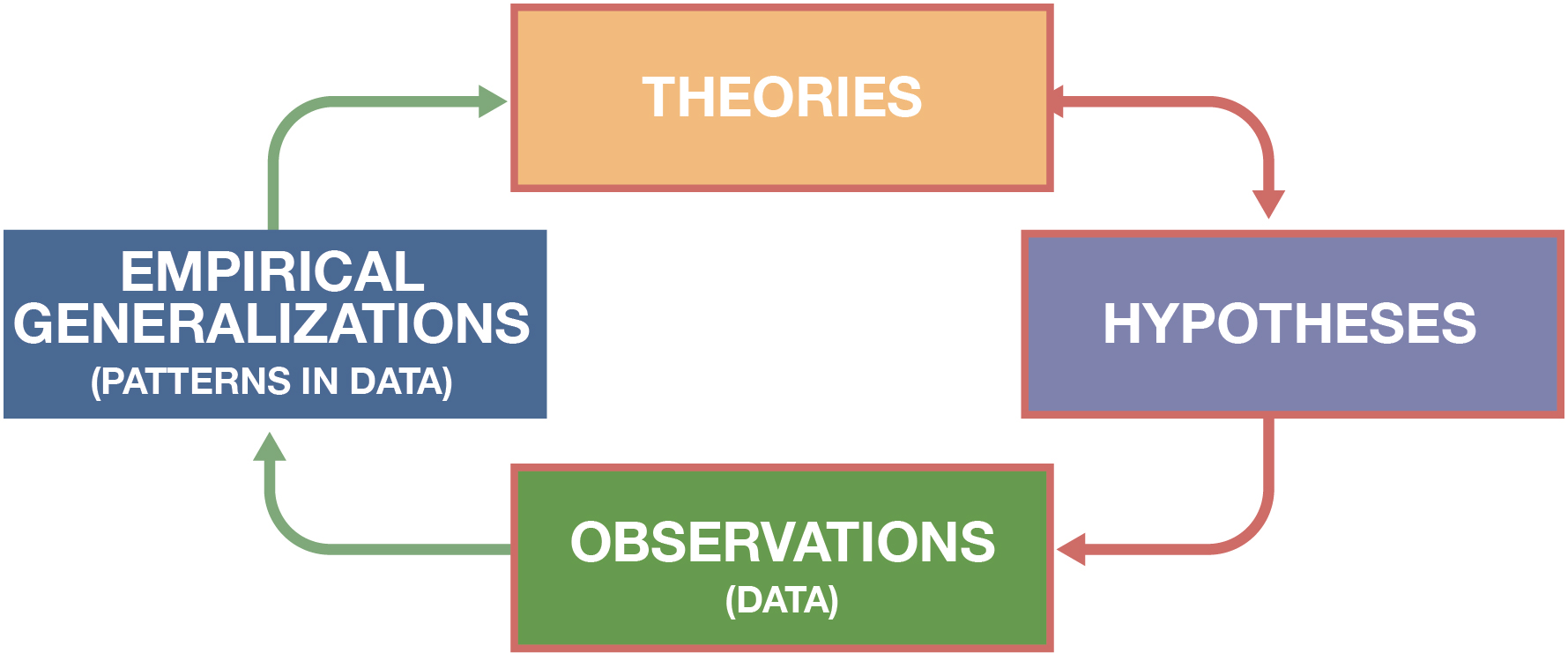

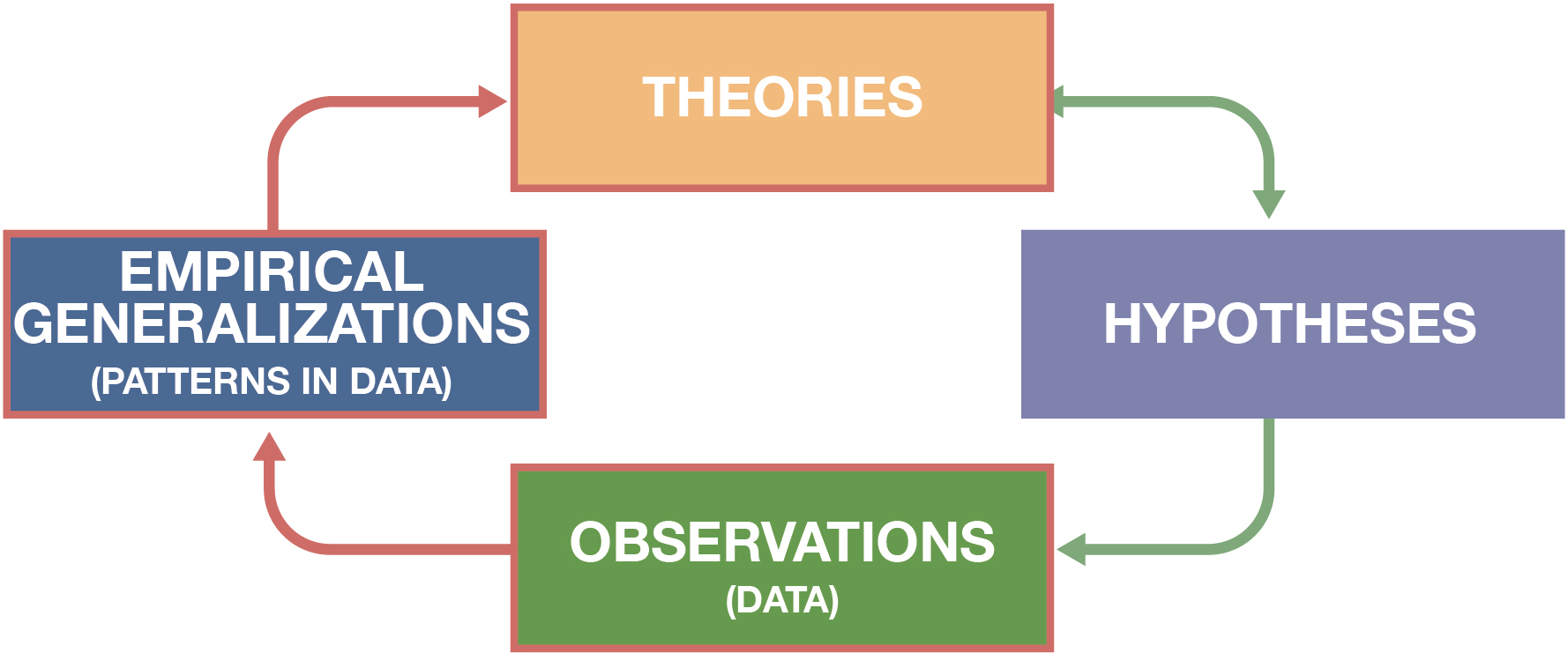

Induction and deduction are often seen as two sides of the coin of scientific research, as you can see visually in Figure 4.2. Combined, they represent what is sometimes called the “Wheel of Science”: a cycle of induction and deduction where one approach picks up where the other left off. As this diagram implies, we scientists constantly shift between theorizing and empirical observations—between induction and deduction—as we learn more about a topic. For instance, we engage in induction whenever we observe something and ask, “Why is this happening?” or “What broader trend is this a case of?” In answering that question, we advance one or more tentative explanations. We then use deduction to test these hypotheses—in the process, perhaps narrowing down our list to the most plausible explanation, based on logic and our understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Let’s go a bit deeper into each of these analytical approaches: first deductive approaches to test theories, and then inductive approaches to generate theories.

Deductive Approaches: Theory Testing

Deduction is the version of scientific analysis that you were most likely taught in school or on educational TV shows. In a deductive study, you start with a theory you want to test. You then apply that theory to a particular context (a particular population), developing one or more hypotheses—expected answers to your research question. Finally, you conduct data collection and analysis and see if your empirical results support your hypothesis. Again, the goal here is to test theories—use systematically gathered data to conclude with confidence that your hypothesis holds up or not. Ideally, you also want to go beyond just confirming or disconfirming the theory at hand, but also refining, improving, and extending it. Among other things, the results of your deductive investigation might allow you to revise your existing theory to say in what social contexts it is valid, and in what contexts it is not.

Let’s consider some examples of deductive research. In their research on hate crimes, Ryan King and his colleagues (2009) tackled a deductive research question: what effect does the locality where a hate crime occurs have on the response of law enforcement to that crime? Based on existing theories about the historical legacies of racial violence in different regions of the country, they hypothesized that law enforcement would respond less vigorously in areas where racial violence had prevailed during the Jim Crow era of segregation—areas that were largely, but not exclusively, in the South. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing county records of lynchings prior to 1930 and modern-day data from the same localities about how police responded to crimes falling under federal hate crime law—specifically, whether law enforcement complied with federal law, whether they reported hate crimes targeting African Americans, and whether they prosecuted hate crime cases. Overall, the authors found support for a modified version of their hypothesis: in areas where lynching prevailed prior to 1930 and where there were substantial African American populations, police responded less forcefully to hate crimes.

In another well-done deductive analysis, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011) studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health (again, note the particular form that this quantitative research question takes: the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable). Based on prior research, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that poor classroom environments—where students lacked basic supplies or even heat during the winter—would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems among those children. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, underscoring the fact that policymakers needed to pay more attention not just to children’s grades, but also to how their day-to-day experiences in school could affect their mental health.

As social scientists ourselves, we are obviously biased, but we would venture to say that theory testing in the social sciences is generally harder than it is in the hard sciences. (For empirical support of this claim, we refer you to the tweet from physicist Neil deGrasse Tyson in Chapter 1: Introduction.) As we’ve previously discussed, the theoretical concepts that we social scientists use are often hard to define. The tools we have to measure those concepts—questionnaires, observations, and the like—have much less precision than, say, a spectrometer or oscilloscope, given how messy and multivariate human thinking and behavior is. There are many more factors that we have to account for in the complex social worlds we study, all of which may also influence the phenomenon of interest. As a result, it can be very difficult to refute social theories that do not work, because proponents of a particular theory can always point to exceptions or dispute the ways that a phenomenon was measured or evaluated. For instance, for decades countries persisted in organizing their economies according to Marxist theories of communism, in spite of mounting evidence that such approaches failed to promote economic growth and social welfare in a sustainable or even fairly equitable way. From the opposite ideological vantage point, the global financial crisis that spread from the United States to other parts of the world in 2008 failed to convince many policymakers to maintain tougher stands against reckless speculation and fraudulent profit-seeking pursued by Wall Street and the larger global financial industry—which have continued to engage in rampant risk-taking in recent years (Fligstein 2021). Sadly, even a preponderance of social scientific evidence often does not settle heavily politicized debates about important policies: every side can raise objections about the possible limitations of any research that doesn’t favor their viewpoint, given the many potential shortcomings that are inevitably attached to any social scientific study, even well-executed ones. While few, if any, physicists dispute well-tested theories like gravity in any substantial way, there are plenty of social scientists who would argue about the merits of social theories that have presumably been tested with decades of deductive research.

All this said, theory testing remains an essential step in social scientific inquiry. It gives us more confidence that we have arrived at the right story about how the social world works. Sociologists often favor a deductive approach because they feel it puts them on firmer empirical ground: their analysis of the data found (or didn’t find) a relationship, the data came from a representative sample, and, therefore, the relationship exists (or doesn’t exist) in the target population. End of story. However, it is obvious that we need to start with a theory to be able to test it. That is where inductive approaches come in.

Inductive Approaches: Theory Generation

The other major kind of analysis used in scientific research is induction. Whereas deduction starts with the abstract—a broad theory—and moves to the concrete—empirical observations—induction does the exact opposite. In this approach, you start off by collecting data relevant to your topic of interest. Once you’ve collected a substantial amount of data, you then step back to get a bird’s eye view. You analyze the data to see what patterns emerge—for instance, how important variables appear to be related to one another within your sample, and how exactly these factors might be influencing one another. Based on these regularities (what are sometimes called empirical generalizations), you begin to piece together a larger theory that connects concepts in a way that’s consistent with what you’ve actually observed. The theory you generate should help explain the patterns you saw in the data.

As we’ve noted, induction is often the approach taken by qualitative researchers. Pioneers of ethnographic methods used the term grounded theory—discussed further in Chapter 9: Ethnography—to describe their process of generating entirely new theories from a foundation of empirical data. The idea was that you would start with a clean slate—that is, having no theory in mind whatsoever, but letting the facts (data) lead you where they may. Nowadays, most qualitative researchers will consciously build upon or challenge existing theories from the outset (as we will describe later), but induction nonetheless remains central to their approach of data collection and analysis. For instance, Tomás Jiménez (2008) sought to understand how the process of assimilation changed for immigrant groups when the flow of newcomers into the country persisted (a context called “immigrant replenishment”), rather than petering away as it had for earlier generations of European immigrants. He conducted 123 in-depth interviews with second- and third-generation Mexican American immigrants in two cities, asking them about the sorts of incidents that made them feel more or less connected with their Mexican immigrant identities. Inductively, Jiménez identified two broad patterns in his interviews. First, these later-generation immigrants felt their ethnic identities to be more salient when they had personal encounters, or heard local reports, of hostility against immigrants—incidents that were common in a context of immigrant replenishment. Second, many interviewees felt challenged as not “authentically” Mexican when they interacted with first-generation immigrants who spoke perfect Spanish and intimately knew the cultural practices of their home country—incidents also more likely to happen in a context of replenishment. These “intergroup” and “intragroup” tensions appeared to sharpen the boundaries that separated later-generation immigrants from other groups, perhaps explaining why assimilation had become more difficult in recent years.

We mentioned before that deduction is what often comes to mind when people think about what science “is.” Generally speaking, we can obtain more definitive answers to our research questions if we pursue a deductive approach (and use the quantitative methods that typically favor this approach). The questions tend to be more focused, and the samples more representative, which means that deductive studies often fit well with the scientific community’s desire to have its work seen as rigorous and unimpeachable. However, these studies are usually asking different sorts of questions, and as we’ll discuss more in Chapter 7: Measuring the Social World, qualitative studies should be evaluated by different standards than quantitative studies are.

Furthermore, one key strength of inductive research that we want to emphasize is that it doesn’t lock us into one story about what is going on with a particular social phenomenon. As the fictional sleuth Sherlock Holmes said, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts” (Doyle 2009). Because researchers doing inductive research start off by diving into the data, they open themselves up to possibilities they may not have considered at the outset. They can critique taken-for-granted assumptions and unearth previously ignored issues. They can absorb the stories they hear and observe and use that inspiration to theorize thoughtfully about any relationships between relevant concepts. They can easily find themselves surprised by what they encounter—and, in science, that’s a good thing. Without this sort of research (which often fits into the exploratory category we described earlier), we’re left with preconceived notions that may not still reflect the current state of affairs. It reminds us of the joke about the drunk man who dropped his car keys on the street at night and scoured the sidewalk looking fruitlessly for them. When a passerby asked why the man was only looking for them under a nearby streetlamp, and not the dark sections of the sidewalk, he answered, “Because the light is better here.” Deduction helps us better understand what we already know; induction lets us explore in the dark.

How Inductive and Deductive Approaches Complement Each Other

As we have emphasized, induction and deduction are each useful in their own way. Each has limitations. And each builds upon the other, helping bring us to better theories. Inductive research is especially valuable when few theories exist to explain a particular phenomenon, while deductive research is more productive when there are many competing theories, and researchers want to know which works best, and under what circumstances. Induction identifies new patterns, such as relationships between variables, but we typically need to do more in order to say with confidence that those relationships are causal or hold up in the target population (specifically, we need to gather a representative sample and rule out any alternative causal stories). Likewise, deduction can help us verify that a theory actually applies to the population of interest, but we need to remember that other factors we haven’t fully considered—other theories yet to be generated—may also be at work, and may actually be more decisive.

Indeed, rather than viewing these two processes in a circular relationship, perhaps they can be better viewed as a helix, with each dialectical iteration between theory and data contributing to better theories—that is, better explanations of the phenomenon of interest. Ultimately, we scientists must be able to move back and forth between inductive and deductive reasoning if we are to extend, modify, or overturn a given model or theory—which is how science advances. To that end, sociologists at times will design their studies to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, they might begin a study with the plan to only conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then they discover along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate their findings.

An example of the latter situation is a classic study by Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984) of the effects of punishment on deterring domestic violence. The researchers decided to examine domestic violence as a form of socially deviant behavior. Based on existing sociological understandings of deviance, they sought to test two theories that seemed to explain whether an accused spouse batterer would respond to an arrest by engaging in more or less abuse. Deterrence theory predicts that arresting accused batterers will reduce future incidents of violence because they seek to avoid future punishment. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused batterers will increase future incidents because the act of arresting them compels them to internalize that deviant identity. Table 4.1 summarizes the two competing theories and the predictions that the researchers set out to test. To see which theory provided a better explanation, Sherman and Berk conducted an experiment with the help of local police in one city. They found that arrests were in fact followed by fewer incidents of reported violence—in line with the predictions of deterrence theory.

Table 4.1. Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery: Testing Theories through Deduction (Sherman and Berk 1984)

| Theory | Prediction |

| Deterrence theory | More arrests → more incidents of domestic violence |

| Labeling theory | More arrests → fewer incidents of domestic violence |

After conducting this study, Sherman and Berk and other researchers went on to conduct similar experiments in six other cities (Berk et al. 1992; Pate and Hamilton 1992; Sherman et al. 1992). Results from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed, but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. The researchers thus turned to control theory, which predicts that the social ties provided by marriage and employment give certain accused batterers a greater stake in conformity. Table 4.2 summarizes the propositions that control theory puts forward about the relationship between arrests and future incidents of violence, which the theory predicts will shift depending on whether accused batterers are married and employed. (To use the lingo we described in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research, marriage and employment here are moderating variables, altering the relationship between arrests and future incidents of domestic violence.) Inserting control theory into their analysis provided the researchers with a superior explanation that better fit the complex nature of the relationships being studied.

Table 4.2. Predicting the Effects of Arrest on Future Spouse Battery: A New Theory Generated from Induction

| Theory | Prediction |

| Control theory | More arrests → fewer incidents of domestic violence for the married and employed More arrests → more incidents of domestic violence for the unmarried and unemployed |

As Sherman and Berk’s original paper and their follow-up studies show us, we as social scientists need to be willing to adapt our analytical approach to the question that is currently before us. In their case, they started with a deductive approach to research but were later confronted with new data that they had to make sense of. In response, they moved to an inductive approach.

We want to wrap up this discussion of analytical approaches by talking about how qualitative and quantitative research approaches figure into this back-and-forth movement between induction and deduction. As we’ve noted, induction is focused on generating theory—developing a model for how the social world operates. After you’ve generated the theory, other (deductive) studies can then test hypotheses derived from it in other social contexts—hopefully, by using representative samples that will produce truly generalizable results. A common approach is for a qualitative inductive study to generate the initial theories, and a quantitative deductive study to test them. But the studies on domestic violence we just described utilized quantitative methods, which brings us back to the caveat we stated at the outset: characterizing qualitative work as inductive and quantitative work as deductive is a simplification. Sometimes quantitative researchers use exploratory and inductive approaches, and sometimes qualitative researchers use deductive approaches. The formats for qualitative and quantitative research questions we proposed earlier are just templates to get you started, and good research questions will crop up that don’t fit into these cookie cutters.

Furthermore, characterizing qualitative work as always inductive—always about generating theories—can lead people to undervalue the difficult work that skilled qualitative researchers do, portraying it as simply a matter of generating ideas that “real” social scientists (quantitative researchers) go on to test. As we hope we’ve made clear, inductive research is important in its own right. We can only test what we already know, and induction allows us to be surprised by what we observe in the real world. Qualitative work is especially useful when we are confronted with new phenomena and complex causal relationships—when we still need to tease out how one factor affects another, how processes build upon each other, and how feedback loops and reverse causation may be influencing our results.

All that said, qualitative sociologists can shift into a more deductive mode of analysis when they are gathering data in the field. Even within the same study, they can move between modes of discovery and validation (Wilson and Chaddha 2009). When they are in a “discovery” mode, they are identifying patterns and crafting new theories in the inductive fashion we’ve previously described. When they are in “validation” mode, however, they look for any cases that contradict the theories they have generated so far—that don’t fit the patterns they’ve earlier identified. They then try to explain these outliers, refining the theory at hand to account for them. This latter strategy doesn’t give us as much confidence about the existence or nonexistence of causal relationships as well-done deductive studies—with their representative samples—would, but it can tell us about contexts where a phenomenon does not apply, and help us understand why. In doing so, it fits with the advice of the sociologist Charles Ragin (2023), who argues that there are no real “negative” cases—instances that don’t fit into your theory—but only “positive” cases that have yet to be matched with the particular theory that explains them.

We noted earlier the tradition of grounded theory in ethnography, which takes a purely inductive approach: ethnographers enter the field with no preconceived notions and knit together new theories fashioned solely from the data they collect. There is something to be said for this open-minded orientation toward fieldwork, which can allow us to arrive at highly original and unconventional theories. However, the truth is that even qualitative researchers who favor inductive investigation rarely take such an extreme stance. More often than not, they bring certain theories into the field, which help them figure out what sorts of questions to ask or what sorts of observations to conduct. In fact, some qualitative researchers favor a hybrid approach known as abduction. In this type of empirical investigation (to simplify), researchers apply a particular theory to the social context they’re examining and then look for outliers, or deviations, from that theory. (Here, qualitative researchers are pushing hard on the “validation” strategy that we just described.) They then attempt to explain those outliers, refining the theory and making it more complex and comprehensive. Searching for empirical surprises in this way is therefore not just about generating new theory, but also about testing—to the extent possible with the limited sample at hand—whatever previous theorizing has proposed.

Key Takeaways

- Whether a researcher takes an inductive or deductive approach will determine the process by which they attempt to answer their research question.

- The inductive approach involves beginning with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- The deductive approach involves beginning with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive approaches to research complement one another and can be employed together—even, at times, in the same study—for a more complete understanding of the topic that a researcher is studying.