7. Measuring the Social World

So far, you have learned how to generate a working research question to guide the design of your proposed study. You’ve also learned how to identify a sample to study to answer that question. What happens next?

So far, you have learned how to generate a working research question to guide the design of your proposed study. You’ve also learned how to identify a sample to study to answer that question. What happens next?

The first step is the conceptualization process, which we touched on in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research. As a review, let’s walk through the process of conceptualization for a hypothetical research question. Imagine you were going to embark on a project to research students’ perceptions of traditional male and female gender roles. How would you go about conceptualizing what you mean by “gender roles”? Here is one plan of action:

- Consider what you really want to know about the topic of male-female gender roles. You could start by brainstorming ideas with other students and reading some literature reviews on the topic (see Chapter 5: Research Design).

- Your efforts should lead to the gradual development and refinement of a research question. As mentioned in Chapter 4: Research Questions, this process is iterative—that is, you will continue to edit and improve your research question, particularly as you consult the relevant literature. Let’s say that the research question you eventually come up with is, “What is the relationship between students’ attitudes about traditional gender roles and their future career plans?”

- As you refine your research question, you will want to identify any concepts that relate to it, along with any relevant dimensions of those concepts (see the discussion of multidimensional concepts in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research). You should then define your key concepts of interest. For the research question we just proposed, you might define “traditional gender roles” as the “commonly expected characteristics and behaviors determined by an individual’s socially assigned gender at birth.” “Career plans” might be defined as the “profession that a person ultimately hopes to pursue.”

- Create a conceptual map (see Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research) of how the concepts you have described might relate to one another. Ideally, you will be able to use existing theories and research results to get an idea of the possible relationships at hand.

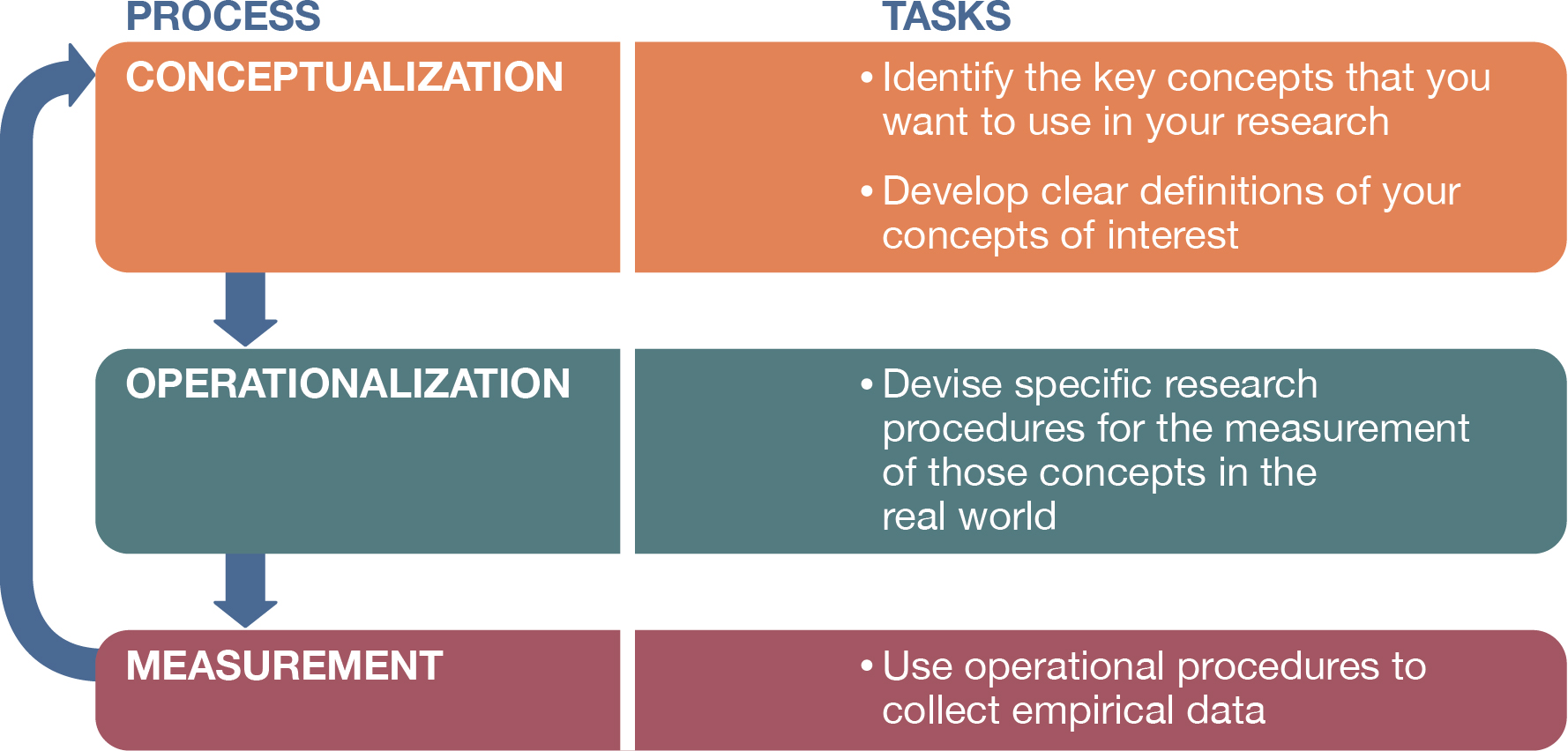

After you clarify the nature of the concepts relevant to your research question, what do you do next? Figure 7.1 shows you the process that typically unfolds for researchers. After conceptualization, comes operationalization. (Yes, we agree, this word is a mouthful—like “Mississippi,” it takes some practice for it to roll off your tongue. For starters, put your stress on the ra and za syllables.)

In the process of operationalization, researchers state precisely how a concept will be measured. You can think of operationalization as the answer to the question, “What procedures will I use to measure this concept?” Specifically, you will want to operationalize—make choices about how to measure—any concepts that relate to your research question. Then you can go out and measure those concepts in the real world.

As we discussed in Chapter 3: The Role of Theory in Research, operationalization is about converting our concepts into measurable variables. (Confusingly, many social scientists use the term “variables” when they really mean “concepts”; as we noted earlier in the textbook, “variable” has become a shorthand for both conceptual and operational definitions.) A variable can also be called an indicator or a measure. Qualitative researchers rarely use the terms “variable” or “indicator,” which are associated more with quantitative analyses, but at the end of the day they, too, are interested in finding ways to describe abstract concepts as they manifest themselves in the real world.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the procedures of operationalization and measurement and some of their pitfalls. As you dive into this work, one thing you should keep in mind is that your strategy for data collection will help determine your strategy for operationalization. A survey implies one way of measuring concepts, while conducting a focus group or ethnographically observing people’s behavior requires quite different ways of measuring them. Your choice of a sample (what we discussed in Chapter 6: Sampling) will also influence your decisions about what sort of measures you can reasonably employ.

Another thing to keep in mind is that you may need to adapt and revise your measures as you learn more. The conceptualization-operationalization-measurement (COM) process we’ve described usually follows that order, with the earlier stages influencing those that come later. Sometimes, however, you’ll find yourself moving back and forth between these steps. For instance, you may return to your research question and perhaps even its concepts as you think through what you can feasibly measure in the real world. After you collect data, the findings from your analysis may suggest to you that you need to refine your concepts—and the entire process may need to begin again. This is especially the case for qualitative research, in which the reworking of both concepts and measures is often the point of the study. For instance, you might want to learn how members of a group actually understand a concept, or how best to measure it in the real world, which means the measures you start with might not be those you end up with. While revising measures after data collection is more problematic in quantitative research, it is sometimes called for, too. As we’ve emphasized, conducting social research is not always linear or straightforward—and that goes for how we measure the social world as well.

Opening chapter image credit: NASA. Adapted by Bizhan Khodabandeh.