12. Experiments

12.4. Field Experiments: External Validity at the Cost of Control

Learning Objectives

- Describe the key characteristics of a field experiment.

- Describe the methodological approach of an audit study.

A key strength of laboratory experiments is the high level of control that researchers have over what goes on in the study. Typically, they can direct the recruitment of participants, manipulate the independent variable directly, and decide on when and how to measure the dependent variables. Yet, as we discussed earlier, laboratory experiments are often conducted under conditions that seem artificial. The social processes uncovered under such conditions may not be generalizable to life outside the lab.

Field experiments are conducted in the field—that is, in an actual organization’s office or an actual city’s labor market. They are often used to gauge the effectiveness of a social intervention, such as a health, social welfare, or educational program. Because field experiments gather their data from real-world settings, they have higher external validity than their laboratory counterparts. But this strength of field experiments is also their weakness, because real-world settings cannot be controlled as easily as lab settings can be. And because field experiments tend to be costly to conduct and may even require the cooperation of outside parties like government agencies, researchers without a lot of funding and other external support are particularly constrained in what they can do.

For one thing, conducting a field experiment often makes it hard or impossible for the researcher to randomly assign participants into experimental and control groups. Emily Becher and her colleagues (2018) conducted a field experiment to evaluate Parents Forever, a University of Minnesota divorce education program developed in the 1990s to improve parental well-being, coparenting, and parent-child relationships following a divorce. However, the researchers did not have access to a randomly assigned control group. The divorcing parents participating in Parents Forever had been court-mandated to attend a two-hour divorce education program. If they were going to be the experimental group—providing evidence of Parents Forever’s effectiveness—then the researchers would need to compare their outcomes to a sample of similar parents also going through divorce but not in that program. To construct this control group, the researchers recruited divorcing parents through an online platform providing workers for hire. As the researchers themselves acknowledged, this approach was not ideal, and in their study they referred to the group recruited online as a “comparison group” rather than a “control group” to recognize how it fell short of the classical experimental ideal. (We’ll discuss comparison groups and the quasi-experimental approach of studies like this one in greater detail later.) While the researchers ended up with two groups of divorcing parents to compare, the demographics of the two groups were notably different. Specifically, the comparison group was more racially diverse and more educated than the participants recruited from the Parents Forever program.

All of the study’s participants completed a pre-survey and a follow-up survey three months later, which found that the Parents Forever program led to improvements in parenting practices, adult quality of life, self-efficacy, and child conduct problems and peer problems. These results, however, may have been skewed by the fact that the field experimenters were not able to recruit randomly selected control and experimental groups. Among other things, the higher degree of diversity and education in the comparison group might itself have accounted for some of the observed outcomes that the analysis credited to the program.

Even when it is possible to use random assignment to experimental and control groups in a field experiment, the lack of control that researchers have over conditions on the ground means that their best-laid plans often go awry. For example, researchers Lawrence Sherman and Richard Berk (1984) conducted a field experiment to test two competing theories about whether criminal punishment deters domestic violence. According to deterrence theory, punishment should reduce deviance—and thus arresting an accused spouse batterer should reduce future incidents of violence. Labeling theory, however, predicts the opposite, arguing that the act of arresting the alleged perpetrator will only heighten their self-identity as a batterer and therefore lead to more violence.

Remarkably, the researchers were able to convince the Minneapolis police department to help them determine which theory held up—that is, whether arresting alleged perpetrators actually reduced subsequent reports of domestic violence. The police department agreed to implement a policy of randomly choosing among three responses to domestic violence calls: arresting the accused batterer, ordering the accused to leave the residence for eight hours (separation), or offering mediation (advice). By introducing this randomization, the researchers essentially created experimental and (two) control groups, allowing them to see whether arrests were more or less effective than the other two responses in reducing future violence. This analysis found that arrested suspects were less likely to commit further acts of violence over the next six months than those who were ordered to leave (according to official data) and those who were advised (according to victim reports).

Unfortunately, the randomization was not as successful as the researchers had hoped. Police officers did not reliably follow the protocol they had been given. They would leave the study instructions at the station. They would misunderstand or ignore what they were supposed to do. Officers were much more likely to follow through on their randomly chosen directives when it involved arresting the accused perpetrator: they did so 99 percent of the time, but only 78 percent of the time when instructed to provide advice, and only 73 percent of the time when instructed to separate the alleged batterer from the residence. The implementation problems that the researchers experienced meant that their sophisticated research design failed to perform as well as it could have, hampering their ability to rigorously assess whether arrests did or did not lead to more incidents of domestic violence. (Essentially, the researchers were dealing with attrition bias: cases in their sample were dropped disproportionately from the control groups, meaning that the effect of not arresting alleged batterers could not be accurately measured.) For instance, it may have been that when officers encountered cases of spousal abuse that they perceived as especially severe, they were more likely to ditch any instructions to the contrary and go ahead and arrest the accused batterer. These severe cases would be more likely themselves to be followed by further incidents of domestic abuse, and yet they were disproportionately dropped from the control groups of separation and advice, thereby overstating the effectiveness of such non-arrest responses in reducing future violence.

The Minneapolis domestic violence study underscores how field experimenters have less control over the conditions of the experiment than those working in laboratories. With enough resources and institutional support, however, it is possible to create field experiments that adopt all aspects of classical experimental design and minimize threats to internal variety in a robust fashion. Consider the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) study, a celebrated field experiment conducted in the 1990s that examined whether having residents of poor neighborhoods move to higher-income areas improved various life outcomes, especially for children. Sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the study recruited 4,600 low-income families with children who were living in public housing projects. Even though the study was a field experiment, the researchers were able to implement a randomized controlled experimental design. They used a lottery to assign the families who volunteered for the study into one of three groups. One group received housing vouchers that for the first year could only be used to move to low-poverty neighborhoods. They also received counseling to help them find homes in these neighborhoods, and after a year, they could use their vouchers to move anywhere. The second group received housing vouchers without any geographic restrictions, but they did not receive any counseling. A third group did not receive vouchers but remained eligible for other forms of government assistance.

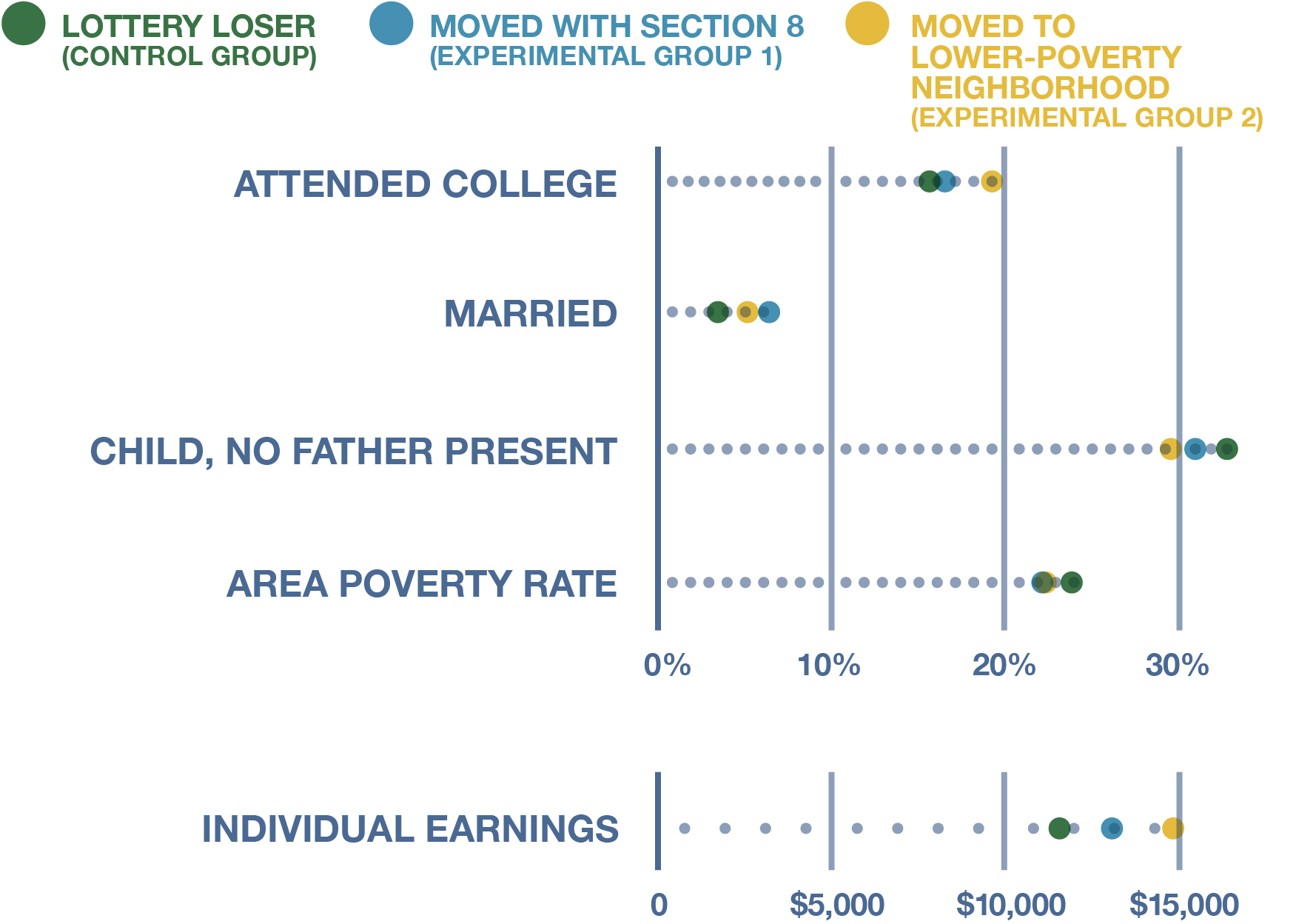

Early results were mixed, but a later analysis of the study’s longitudinal data (depicted in Figure 12.7) by the economists Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz (2016) found that those children who moved at a young age to low-poverty neighborhoods had later earnings that were, on average, a third higher than what children who didn’t move wound up making as adults. These children were also more likely to go to college and grow up with a father present. (The same benefits did not accrue to children who moved when they were 13 or older, which helped explain some of the study’s previous, mixed results: whether the vouchers made a difference for children appeared to depend on whether they moved early enough to have meaningful exposure to a low-poverty neighborhood during their most formative years.) Children in families that received unrestricted housing vouchers also saw improvements over non-movers, yet not to the same extent as for that first group. These experimental findings provided strong causal evidence in support of the view that the neighborhood where a child grows up decisively shapes their later life outcomes (Wolfers 2015).

An important aspect of field experiments like MTO that evaluate policies is they do not just give the treatment (the housing voucher, the income support, etc.) to everyone. Insead, they have a lottery, with the lottery winners winding up in the experimental group (who receive the program’s benefits) and the lottery losers serving as a control group. This enables researchers to rule out alternative factors and precisely measure the impact of the policy itself. Because the evaluation described above of the Parents Forever divorce education program did not have such a lottery for entry into the program, it was much harder for researchers to say that any improvements they saw among the program’s participants were due to the program and not preexisting differences between that group and the cobbled-together comparison group.

Audit Studies: A Powerful Test of Discrimination

One frequently used type of field experiment is the audit study. Social scientists typically employ audit studies to test discrimination in the labor market, the real estate market, and other settings. The researchers will hire and train testers (also known as auditors) who are matched on all characteristics except one—for instance, gender or race—so that the study can see if the testers are treated differently based on that sole characteristic. The testers then go undercover into the particular setting being studied, strictly adhering to the behaviors modeled for them by researchers so that any bias they experience can be attributed solely to discrimination. This covert experimental approach is a very effective way to understand how discrimination operates in the real world, especially in comparison to methods like in-depth interviews and surveys where respondents have strong incentives to hide racist or other socially undesirable attitudes.

‘Fair housing groups and activists pioneered housing audits in the 1940s, and government agencies like the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) eventually adopted the strategy, conducting in-person audits to gauge levels of discrimination in rental and housing markets (Gaddis and DiRago 2023). Think tanks like the Urban Institute later applied the approach to studying discrimination in hiring. Over the last several decades, the shift toward applying online for jobs and housing has made it easier for researchers to conduct large-scale audit studies—by electronically disseminating materials for fictitious job candidates, for instance, rather than training closely matched auditors and sending them into the field.

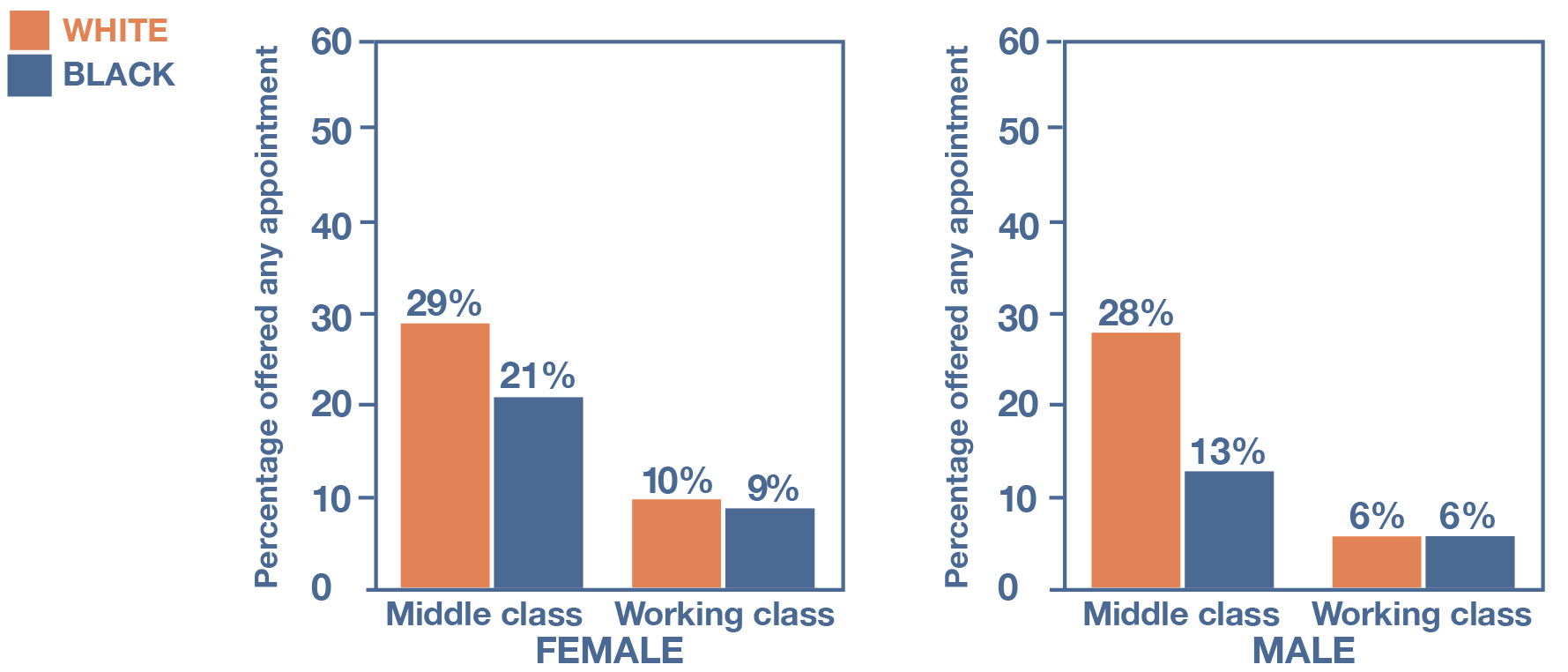

The audit methodology has also been extended well beyond its original domains of housing and job markets. Heather Kugelmass (2016) used it to study whether mental health therapists discriminated against certain types of people when accepting new patients. She hired a group of voice-over professionals as auditors and gave them a script for requesting a therapy appointment over the phone. These auditors adopted racially distinctive names and used speech patterns that signaled their racial and class backgrounds. They then called 640 psychotherapists randomly drawn from a private insurer’s directory and left messages asking for help with their depression and anxiety.

As the audit methodology requires, the study’s help-seekers presented themselves in the same way across every relevant characteristic and behavior except those relating to their class, gender, and race. All of them named the same health insurance plan. All of them requested a weekday evening appointment. And all of them asked the therapists to leave them a voicemail message with any available appointment times. As it turned out, therapists were much more likely to offer an appointment to white middle-class help-seekers (see Figure 12.8). The gender of the help-seeker didn’t appear to affect whether therapists returned their calls, but women did get more appointment offers for the preferred hours.

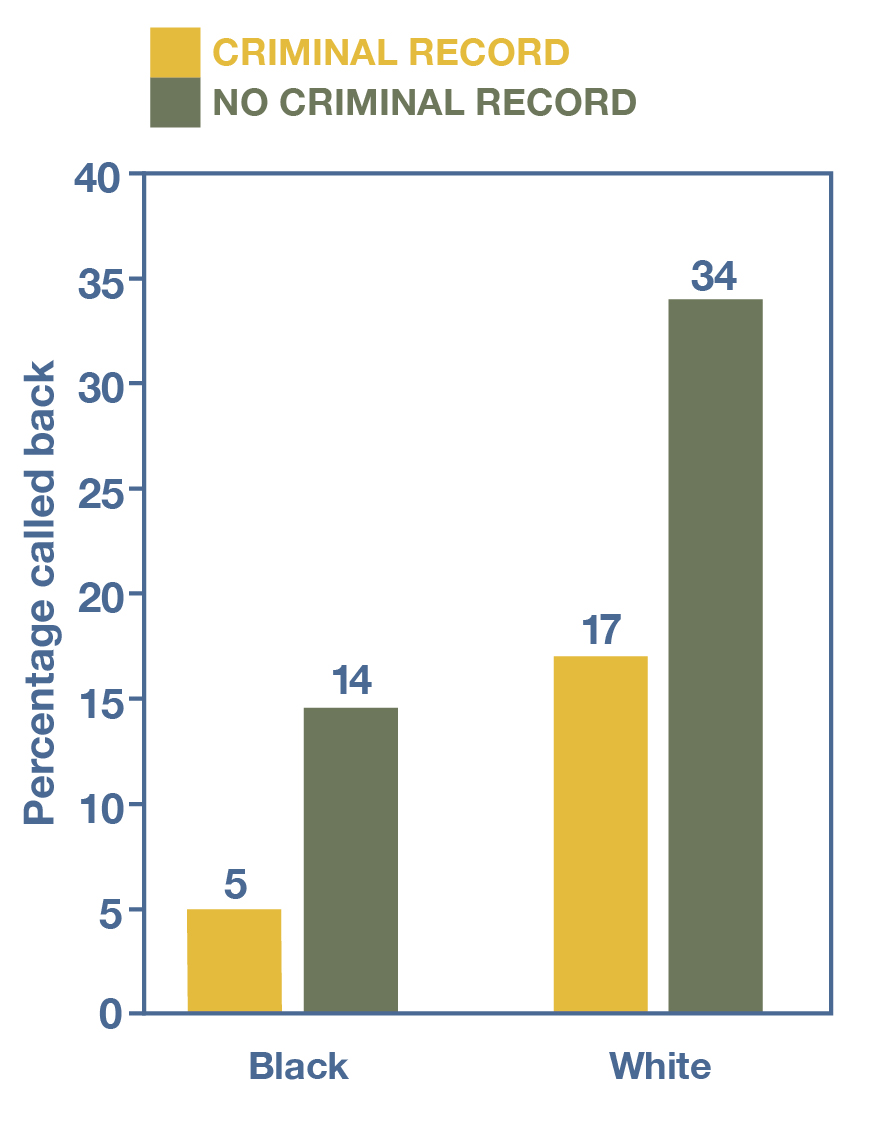

A series of influential studies using the audit methodology were conducted by the late sociologist Devah Pager and her collaborators starting in the early 2000s. For her American Journal of Sociology article “The Mark of a Criminal Record” (2003), Pager hired four young men to pretend to be job applicants for a wide range of entry-level jobs. Every week, they applied to 15 openings advertised in local job listings, auditing 350 employers in total by the end of the study. The four auditors—“two blacks and two whites”—were all college students who were 23 years old and “matched on the basis of physical appearance and general style of self-presentation” (946–947). Characteristics of their actual educational attainment and work experience were tweaked so that they were similar for the purposes of applying for jobs. Furthermore, among the two testers of each race, one was randomly assigned a “criminal record” for the first week: a felony drug conviction and 18 months of served prison time, which they would dutifully report to employers. (Compare the approach here to the random assignment of parental status in the “motherhood penalty” study.)

The pair of testers then applied to the same jobs, one a day after the other, with the sequence randomly determined. Testers would visit the employer, fill out applications, and then see if they received a positive response, or “callback”—which could take the form of either a job offer on the spot or a phone call later on from the employer on a voicemail number set up for each tester. Every week, the criminal record was rotated among the racially matched pair.

What was the point of this matched and randomized setup? Pager wanted to isolate just the effect of race and just the effect of a criminal record on whether employers would hire a job candidate. With the treatment of the “criminal record” randomly applied to the pair of racially matched testers and changed every week, Pager could plausibly chalk up any differences in hiring outcomes to the criminal record itself, rather than anything she had missed in matching the testers on every relevant characteristic.

As shown in Figure 12.9, Pager’s audit study found that applicants of either race who had a criminal record were much less likely to receive callbacks. Perhaps what was most shocking, however, was that the African American testers received so few callbacks. In fact, while only 17 percent of the applications by white testers with criminal records resulted in callbacks, only 14 percent of those by African American testers with clean records did so. “This suggests that being black in America today is essentially like having a felony conviction in terms of one’s chances of finding employment,” Pager said in a 2016 interview (Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality 2016).

Pager and her colleagues reinforced and expanded on these findings in subsequent studies. For example, in a comparable audit study that she, Bart Bonikowski, and Bruce Western (2009) conducted in New York City, they hired white, African American, and Latino men to pretend to be job applicants. As in Pager’s previous study, the testers were matched on a variety of characteristics and trained in the audit protocol. Then the researchers sent the men out to apply for entry-level jobs—this time, the same jobs—with equivalent résumés. Again, they found that white applicants received far more callbacks, and both African American and Latino applicants without criminal records did no better than white applicants just released from prison. A particularly interesting aspect of this later study was its qualitative component: the multiracial group of testers wrote down field notes describing their encounters with the same employers, and that ethnographic data gave the researchers some insight into how employers were making their decisions about hiring in ways that disadvantaged nonwhite applicants. For instance, the nonwhite testers would report being told that a position was already filled, while the white testers would be offered the same job later on. Nonwhite applicants would be asked to fill lower-status positions from the ones they originally applied for (bussers rather than servers, for instance), while white applicants were at times upgraded on the spot (asked to take jobs, say, as managers). This study’s mixed-methods approach exemplifies how experiments can deftly incorporate qualitative data like the observations of an audit study’s testers, allowing researchers not just to infer causality but also to illuminate the causal mechanisms that might bring about a cause-effect relationship.

Pager died in 2018 at the age of 46 from pancreatic cancer, but the remarkable findings from her audit studies have influenced the ways we think about race, incarceration, and economic opportunity (Seelye 2018). The huge effect that race by itself had on employment outcomes across these studies was hard for even skeptical writers to refute, given the robust experimental design that Pager and her collaborators utilized, which accounted for every relevant alternative explanation. And the persistent finding that a felony conviction for drug possession could dramatically curtail employment opportunities helped generate public pressure on behalf of the so-called ban-the-box movement, which seeks to convince employers to stop asking about felony records on job applications. Large corporations like Walmart and Home Depot have now removed this question from their applications, in part due to the important work that Pager did.

The Tradeoffs of Conducting Field Experiments versus Laboratory Experiments

Now that we’ve seen the many types of field experiments that social scientists can profitably conduct, let’s talk a bit more about how laboratory and field experiments differ from one another—and how they might complement one another. Recall the “motherhood penalty” study (Correll et al. 2007) that we described in the last section. However striking the findings of the lab experiment were, critics might say that getting undergraduate students to “play” at making hiring decisions doesn’t give us a plausible sense of what actually goes on when actual hiring managers look over actual résumés. Among other things, the study participants didn’t have work experience in the relevant industry, which might mean stereotypical thinking figured more into their decisions than it would for actual hiring managers.

Perhaps anticipating these criticisms, the study’s authors actually ran a field experiment in addition to their lab experiment. In response to newspaper job listings in a Northeastern U.S. city, the researchers submitted two sets of fake résumés and cover letters on behalf of equally qualified job applicants, based on the templates already used for the fictitious marketing director position. One of the candidates was randomly assigned to be flagged as a parent in the job materials, and the two candidates for each position were of the same apparent gender (as signaled in their names). As in the lab experiment, the cues about the candidates’ parental status were subtle—for instance, the résumé for the parent indicated they were an officer in an elementary school PTA, while the résumé for the nonparent said they were an officer in a college alumni association. The researchers then waited to see if these fake applications received any invitations for a phone or in-person interview. Again, the researchers found that mothers were discriminated against—with nonmother applications receiving significantly more callbacks than mother applications—even though the field experiment did not uncover comparable evidence of a “fatherhood bonus” to match the lab experiment’s findings.

As we’ve pointed out many times, field experiments generally do a better job with external validity than lab experiments do. Yet they do so at the price of experimenter control—which, in turn, may make it impossible to use randomization, control groups, testing, and the other features of classical experiments that, as we described earlier, help maintain a study’s internal validity. We can see some of these tradeoffs at work in the separate field and lab experiments that the “motherhood penalty” researchers conducted, which they explicitly did in order to address each experiment’s weaknesses and thereby provide a more convincing case that their research findings were valid. The field experiment showed that employers discriminated against mothers—the same general finding that the lab experiment uncovered, but one that could be more convincingly generalized, given that the field experiment gathered its data based on interactions with real employers deciding on real jobs. The lab experiment had lower external validity by its very nature, but here the researchers’ control over their research setting meant they could go much further in parsing out the reasons that, say, mother candidates fared worse than nonmother candidates in job evaluations. They could specifically and precisely compare how mothers and nonmothers compared on various measures of competence and commitment, rather than having to rely on the flat yes/no response provided by a job callback in the field experiment. In other words, the lab experiment was better able to get into the heads of the people making hiring decisions and understand the reasoning behind their decisions, while the field experiment, at least in this case, was limited to learning about the decisions alone.

Key Takeaways

- Field experiments employ features of classical experimental design, though they often lack much or any control over the real-world settings where they are conducted.

- Audit studies typically are used to test discrimination in the labor market, the real estate market, and other settings. The researchers will hire and train testers who are matched on all characteristics except one—for instance, gender or race—so that the study can see if the testers are treated differently based on that sole characteristic.