9. Ethnography

9.2. Going into the Field

Learning Objectives

- Discuss grounded theory and the extended case method and how ethnographers utilize these approaches when entering the field.

- Describe the factors you should consider when choosing and gaining access to a field site.

- Explain the role of reflexivity when conducting observations in the field.

As we mentioned in Chapter 4: Research Questions, qualitative research typically involves an inductive process—put simply, connecting the dots between aspects of different observations, and seeing what theories emerge as a result. Sometimes ethnographers (and other qualitative researchers) conduct a kind of “pure” inductive analysis called grounded theory (Charmaz 2006; Glaser and Strauss 2017).[1] In this approach, researchers begin with an open-ended and open-minded desire to understand a social situation or setting, letting the data guide them rather than guiding the data with a set of hypotheses in mind. The goal when employing a grounded theory approach is to generate theory. Its name not only implies that discoveries are made from the “ground up,” but also that any theories that emerge are actually grounded in a researcher’s empirical observations and a group’s tangible experiences, rather than being merely theorized into existence. In fact, to ensure that the theory is based solely on observed evidence, the grounded theory approach asks that researchers put aside their preexisting theoretical blinders while they are in the field and afterward, letting the data alone dictate the theory that emerges.

As exciting as it might sound to generate theory from the ground up, the experience can also be quite intimidating and anxiety-producing, as the open nature of the process can sometimes feel a little out of control. Without hypotheses to guide their analysis, researchers engaged in grounded theory work may experience feelings of frustration and angst. For that reason, many ethnographers take hybrid approaches that stand somewhere between grounded theory and hypothesis-driven social science. One popular method that creatively uses existing theory as a departure point is the extended case method, pioneered by the ethnographer Michael Burawoy (1998, 2009). Generally speaking, this strategy involves finding a theory that somehow fails to explain what is occurring in a particular social context. The ethnographer then embarks on a case study, conducting observations within that site to understand why the theory falls short—and how it can be “rebuilt” to accommodate this deviant case. Burawoy pursued this approach in his ethnography Manufacturing Consent (1979), a groundbreaking study of factory workers. Marxist theory predicted that workers would organize to resist their oppression, but Burawoy described how workers’ energies were instead diverted to a “game” of meeting production targets, which blunted any collective resistance to management.

The general approach you decide to take to qualitative research—essentially, how inductive or abductive your inquiry will be—will, in turn, shape two practical decisions you need to make before entering the field: where you will observe (i.e., your field site) and what role you will take while in the field. Let’s talk about these considerations and what other factors will figure into your plans for fieldwork.

Choosing a Field Site

Where you observe might be determined by your research question, but because ethnography is often exploratory and inductive, it can be acceptable to jump into your observations even before you have settled on a focused question. You may enter the field with just a vague notion of the topics you want to study, homing in on a specific set of research questions after you have collected data. Even if you begin with a pointed question in mind, you should remain open to the possibility that your focus may shift as you see what happens in your field site—remember, one of the strengths of ethnography is its ability to surprise you.

Regardless of how focused you are at the outset of your ethnographic study, you should consider the following when choosing a site to observe:

- What do you hope to accomplish with your research?

- What is your topical or substantive interest, and where are you likely to observe behavior that has something to do with that topic?

- Will your observations be limited to a single location, or will you visit multiple locations?

- How likely is it that you’ll actually have access to the locations that are of interest to you?

- How much time do you have to conduct your observations?

Questions 2 and 3 should make you think of the discussion in Chapter 6: Sampling about purposive sampling. You should choose a field site that will give you a useful window into the phenomenon you’re studying. Maybe you want to choose two or more sites that differ in key ways, so that you can compare how that variation influences what you see in each setting. The site or sites you pick do not necessarily have to be “average” cases of your population of interest—say, an “ordinary” neighborhood in a particular city or a “typical” company in a particular industry. Choosing such a site might make it easier to justify the importance of your study, but as we’ve said before, with such a small sample—at most, a few sites—it’s foolish to focus so much on finding a perfectly “representative” case. What’s more, an “average” site may be utterly boring, lacking the kinds of variation that qualitative researchers often find theoretically profitable to explore.

Depending on your research question, you might instead want to study an extreme case of the kind we discussed earlier in the book: a field site that vividly and intensely displays a particular concept of interest. For example, Katherine K. Chen (2009, 2012) chose to study Burning Man, a unique organization that puts on an annual arts festival in the Nevada desert using a deeply democratic form of decision-making and decentralized management. As Chen points out (2015:38), organizations with extreme characteristics can “render visible the invisible,” highlighting for us practices and beliefs that we take for granted, such as “the concentration of power in our everyday organizations, particularly hierarchical ones, and our acceptance of this as normal or even desirable.” By studying an organization without such a concentration of power, Chen put a spotlight on the taken-for-granted work that goes into making an organization run smoothly without stark hierarchies and lots of rules—work that would be much harder to see in an “average” organization.

Questions 4 and 5 get at some of the practical issues that will surely influence which field site you choose to study—or even whether you decide to conduct an ethnography after all. First, the ideal locations to observe may not be available to you. If you’re not observing a public space like a street or park, you will need permission to even step foot onto the property as a researcher. Schools, government agencies, and corporations may refuse you outright or require you to go through an elaborate and uncertain approval process. If you don’t have a person in the organization to vouch for you, you should expect doors to be slammed in your face many times before a single group agrees to consider your request. Note, too, that if an organization extends permission at first but later revokes it, your previous data collection may be compromised, depending on what arrangements you worked out with the group and with your institutional review board (IRB). It may be good to get the organization’s permission in writing (which some presses will want to see before they publish your ethnography, anyways).

If you have a personal connection to any potential field sites, you shouldn’t be shy about tapping those existing contacts or commitments. Perhaps you are already a member of an organization where you’d like to conduct research. Maybe you know someone who knows someone else who might be able to help you access a site. Perhaps you just have a friend you could stay with in that city, enabling you to conduct your observations away from home. While you do need to consider how fair-minded you can be, it can be both fun and personally meaningful to study a group or cause you care deeply about. As Joyce Rothschild pointed out in Chapter 4: Research Questions, that insider knowledge is often your “comparative advantage” as an ethnographer, allowing you to write something that another sociologist couldn’t.

Another key consideration when choosing a field site is your available resources of time and money. As we’ve described, ethnographers take months or even years to collect data at their field sites. Ideally, they are available to visit their site frequently, even daily, so that they get used to the setting—and so that people in that setting get used to them. (In short, ethnography is not a great method to use if you’re looking to do a quick and painless study.) You need to be honest with yourself about how much time you can devote to observing your field site. You also need to think about where you live and whether regular travel to your site is an option for you. Some ethnographers actually relocate so that they can live with or near their population of interest—take Matthew Desmond, who moved into a trailer park and then a rooming house in Milwaukee so that he could study low-income housing issues for his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Evicted (2016). One of the exciting things about ethnography is being able to go to far-flung places and immerse yourself in a previously unfamiliar social world. (In short, ethnography is a great method to use if you are an adventurous person!) Of course, you can still find creative ways to do ethnographic research even if you don’t have the flexibility or funds to pick up and move to the ideal field site for what you want to study.

Collaborating on an ethnographic project might help you address these logistical issues. If you take on one or more research partners, you might be able to cover more ground and therefore collect more data than you could on your own. A research partner could study an entirely different field site (even one in a different part of the world), significantly extending the scope of your study and leveraging a potentially interesting comparison. Having collaborators is especially helpful in ethnography because of the difficult logistical, interpersonnel, and ethical issues you are likely to encounter. You might find it useful to talk through problems or just commiserate with a collaborator who shares at least some of your experiences in the field. Of course, collaborative research also comes with its own set of challenges: possible personality conflicts among researchers, competing commitments in terms of time and contributions to the project (a particularly salient issue in ethnography, given the level of commitment required), and the sociologist’s version of “creative differences”—having clashing methodological or theoretical perspectives that make it difficult to agree on how best to collect data or interpret it (Shaffir, Marshall, and Haas 1980). You should also be aware that building rapport with the community you’re studying might be harder with two or more outsiders involved rather than just one.

Presenting Your Identity as a Researcher

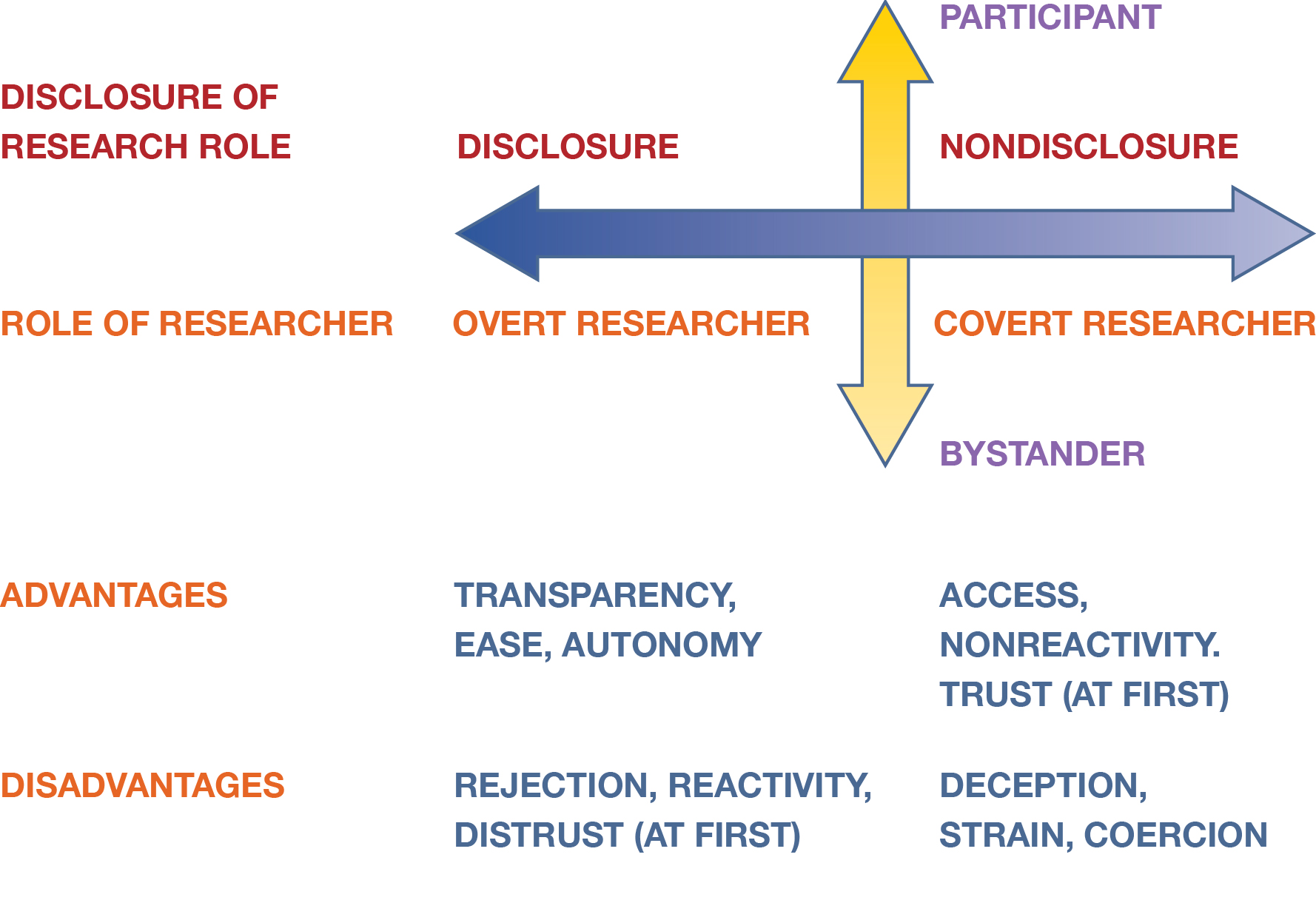

Earlier in the chapter, we discussed the participation continuum and how ethnographers make conscious choices to fall somewhere in that spectrum between being a complete participant and complete bystander. Beyond that general orientation toward the people you are studying, you also have to decide the extent to which you will divulge to them your identity as a researcher. This can also be seen as a spectrum—a disclosure continuum. On one end, you hide your identity entirely (covert research). On the other, you make it known to everyone you observe that you are a researcher (overt research).

In general, not disclosing your identity as a researcher is acceptable when you are observing people in the street or in other public spaces where they have no expectations of privacy. However, some ethnographers decide to be covert while observing in private settings, too. The degree to which they actively hide their identities can differ, with an entirely covert role usually reserved for studying a highly exclusive organization. In this extreme case, they may pretend to be nothing more than participants, and they may deny they are researchers if they are asked.

Entirely hiding your identity from your research participants may seem very appealing because being undercover avoids some of the practical issues we have described throughout this chapter. For instance, some organizations don’t like to be studied, so being open about your observer role means their leaders may refuse your requests to enter those settings. Furthermore, if specific participants are aware that you are a researcher, you may experience some trouble establishing rapport with them, especially when you are dealing with a very closed or tight-knit group of people. You can address this lack of trust by being more of a participant rather than a bystander, or by having an insider at the site who can vouch for you. Inevitably, however, people who know they are being observed will respond in some way to that observation, leading to reactivity that may skew the results of your observation. Depending on the situation, participants may be uncomfortable or even hostile in your presence. Likewise, they may behave differently than they otherwise would have out of desire to maintain a socially acceptable persona, conceal specific unflattering facts about themselves or their group, or even seek your approval as a researcher. If you choose to conduct covert research, all these issues may be mitigated.

As you probably noted, many of these risks are similar to the ones we discussed regarding the degree of participation you take up in the field. Yet it is worth distinguishing the disclosure continuum from the participation continuum in your head because they are conceptually distinct, and different combinations of participation and disclosure are possible. For instance, you can be a bystander observer who doesn’t disclose your identity as a researcher, or you can be a participant observer who is utterly engaged in the organization being studied—though everyone there knows about your research.

Furthermore, falling on the covert side of the disclosure continuum presents a number of unique ethical and practical issues. As we discussed in Chapter 8: Ethics, it is critical for researchers to obtain informed consent from their research participants, which includes not deceiving them about the nature of the research—or about the fact that research is taking place, period. The institutional review board at your school or organization that vets your proposed project may let you move forward with such a study, but expect a lot of pushback. IRBs generally do not allow researchers to deceive respondents unless the rationale is highly compelling and outweighs the harm caused by not obtaining fully informed consent from the outset. (Again, more discretion is allowed when the field site is a public space where people may not have an expectation of privacy.)

Another obvious problem with being a covert researcher is that it introduces a great deal of stress into your field research. You will constantly be worried about being exposed as a researcher and facing the wrath of deceived participants, which further adds to the psychological burden of continual observing and/or participating. Even if this strain is manageable at first, your initial decision to conduct covert research may complicate matters later as your project unfolds. If you choose to conceal your identity, for example, how long will you do so? After all, eventually your work will be published, and then the people you deceived will likely figure out your identity. Should you disclose this fact sometime before then? How might participants respond when they discover you’ve been studying them? If they find out before you’ve had a chance to tell them, they may be even more upset.

A final issue you might encounter in hiding your identity is perfectly summed up in a Far Side cartoon. It depicts a “researcher” dressed up like a gorilla, hanging out with a few other gorillas. In the cartoon, one of the real gorillas is holding out a few beetle grubs to the researcher, and the caption reads, “So you’re a real gorilla, are you? Well I guess you wouldn’t mind munchin’ down a few beetle grubs, would you? In fact, we wanna see you chug ’em!” As a covert researcher, how will you respond if asked to engage in activities you find unsettling or unsafe? For instance, while conducting covert research among right-wing survivalists, Richard Mitchell (1991) was asked to participate in the swapping of violently racist and homophobic stories. He later expressed regret over his involvement in those activities. The degree of coercion you are subject to may be greater if you are a covert researcher, given that you do not have the excuse of “I’m a researcher.”

As you can see, the decision to study a site covertly is not as convenient as it might seem at first glance. That said, you should also note that there is some variation in the degree to which researchers flag their identity as researchers even when they are not seeking to be entirely covert. This is because there is some leeway for not volunteering the fact you are observing someone. Let’s say an organization approves your request to study them. Ideally, the leaders let everyone in the organization know that you are a researcher. At the private meetings of the group that you attend, you can take the extra step to announce your role so that no one is blindsided. Undoubtedly, however, there is going to be more or less awareness of your researcher identity across members of the group. You will have to decide whether you will be more active or passive in making people aware—another reason to think about this process of disclosure as a continuum, rather than an either/or state. For instance, if you happen to observe a large gathering of that organization—say, a protest march they organize—it will be difficult or awkward to convey your role to everyone in attendance, and there wouldn’t really be an expectation of privacy given the public nature of such an event, either. As is often the case in the field, you as a researcher will need to navigate these more nuanced situations that can come up, sometimes unexpectedly, in the course of your observations. You should do with due consideration to both ethical principles and practicality—while still following the bright lines that your institutional review board has set for you in terms of getting explicit approval from those you observe.

Here’s a final point we want to make about being covert: it’s overrated. With persistence, you’ll likely find some group willing to let you openly observe them. And while your known presence as a researcher undoubtedly changes how people act, that effect will lessen with time—another reason that ethnographers spend so long in the field. Specifically, your continual presence and constant vigilance as an ethnographer will, with time, bore even the most circumspect research participant to the point they return to acting like their usual self. Putting up a facade takes some effort, and especially if you are a participant observer, eventually you will become just another part of the scenery to them. (After all, even documentary film crews wielding cameras and boom microphones somehow get their subjects to lower their guard after, say, a few weeks of shadowing them.) Our advice for new ethnographers is patience. Stay calm and keep observing.

Considering Your Identity in the Field

In addition to managing their professional identities in the field, ethnographers also need to manage their personal identities—that is, seriously considering how they will interact with the people they encounter in their field site, and what implications the identities they possess or present will have for their research.

First, as part of the self-critical process of reflexivity mentioned earlier, ethnographers should contemplate how their social location—their identity relative to the people they’re studying—might affect their ability to conduct research at a particular field site. When assessing your positionality, it’s helpful to distinguish between the ascribed and achieved aspects of your identity. Ascribed aspects are involuntary, such as your age and race, and you are stuck with them—even though they may make it easier or harder for you to conduct observations in certain settings. For instance, if you were studying racial discrimination in a particular workforce, you would want to think about how your own racial or ethnic identity might enhance, inhibit, or otherwise affect what you see or how you interpret it. Among other things, individuals from a different background than your own might be wary about what they say around you, and you might not understand the nuances of how people of a different group process the treatment they receive. If you were observing children’s birthday parties, you would need to consider how being an adult (assuming you are not some sociological wunderkind) will affect how the party-goers or their parents react to you. Your very presence as a grown-up might change how the children play around you, for example.

Ethnographers do have some control over the achieved aspects of their identities, which would include the clothes they wear and the mannerisms they display. For instance, they may be able to hide the fact that they come from a middle-class background when they are studying poor or wealthy households (or vice versa). As with the hiding of one’s identity as a researcher, the ethical line here can be a bit blurry, but ethnographers do tend to conceal or mute certain characteristics to fit in when they are in the field. They recognize that sticking out in a particular social context can make it less likely that the community at hand will welcome them into that space or trust them with insider knowledge. They also don’t want people to act differently because they know an outsider is watching them. It’s worth emphasizing that whether a particular identity is a benefit or hindrance really depends on the context. For example, in some cases sharing the fact that you are a student might enhance your ability to establish rapport with participants; in other field sites it might stifle conversation and connection.

As an ethnographer, you will need to decide upon the persona you present to other people while observing them. Not all parts of your identity are equally important, and you may find it quite appropriate to play up some aspects and not others. (For instance, student researchers differ on the extent to which they share this aspect of their identity with other people at their field site.) In general, however, we would counsel you to be authentic. Doing so will keep you from misrepresenting yourself in an unethical fashion, and you’ll be surprised how little people ultimately care about who you are—so long as you are respectful and spend sufficient time with them to gain their trust and acceptance.

As a self-reflexive ethnographer, you should think hard about how aspects of your identity may influence the ways that people treat you in the field, and what access you are able to obtain to the interactions and individuals you wish to study. Raising these questions does not necessarily mean that you should not study those who are different from you, however. There have been countless insightful ethnographies conducted by researchers who were not part of the populations they chose to research. Sometimes, the fact that you don’t fit in can make it easier to navigate a particular social context. For instance, being an outsider may mean you are not perceived as a threat to either side in an organization’s ongoing power struggle. As we alluded to earlier with our fish story, keeping a distance may also make it easier to see certain aspects of a culture that insiders take for granted.

That said, ethnographers today are particularly outspoken about the need for more ethnographies to be done by people who actually hail from the communities being studied. It is a sensitive subject given that ethnography was pioneered by white researchers who chose to observe “exotic” indigenous populations—and, at times, allegedly misinterpreted them. As many sociologists see it, studying a community that isn’t your own adds to your obligation to get things right. You need to cultivate cultural sensitivity and avoid any glib presumptions that you truly understand an experience or viewpoint that isn’t your own.

Having an insider at your site who you can turn to in order to interpret your observations can be helpful in reducing this sort of cultural disconnect. Such insiders are called key informants. Perhaps you already have a connection to a person within the organization being studied, or perhaps you immediately hit it off with a particular individual you happen to encounter in the field. This informant can provide a framework for your observations, help “translate” what you observe, give you important insight into a group’s culture, and assist you in recruiting additional participants to observe or interview. If possible, having more than one key informant at a site is ideal, as one informant’s perspective may vary from another’s—and sometimes an informant may have an incentive to portray their organization in a particular light (particularly if that person represents one side in an internal power struggle). One of the most notable key informants in sociology was the gang leader “Doc” from William Foote Whyte’s classic ethnography Street Corner Society (1943/1993). Critics of the book wondered, however, if Doc provided Whyte with a lopsided picture of the dynamics on the North End’s streets. Subsequent efforts to pin down the actual story have challenged whether Whyte faithfully conveyed Doc’s take on the neighborhood to begin with (Boelen 1992).

Although we have talked about the various ways your personal identity affects your research throughout this section, we want to conclude by cautioning you about strategizing too much about your presentation of self in the field. Multiple approaches can work (or not work). Ethnography is more of a marathon than a sprint, and you may make inroads into a social circle on one day, only to see the rapport you built disintegrate on another day. One basic piece of advice is to follow your gut—and your gut sense of right and wrong—when choosing how to interact with other people in the field. Participant observation is a demanding endeavor, and there are sometimes no easy or straightforward answers to the strategic and ethical challenges you’ll encounter. The main thing is to treat others ethically while advancing your research.

Video 9.2. Street Corner Society, in Retrospect. This is a 40-minute interview with William Foote Whyte and several of his research participants nearly forty years after the publication of his groundbreaking ethnography Street Corner Society (1943/1993).

Ethnography as Empathetic Understanding: A Q&A with Amy L. Best

Amy L. Best is a professor of sociology at George Mason University who studies youth and gender identity formation, social inequalities, and school and consumer culture. She has written three ethnographies that immerse readers into the social worlds of teenagers and young adults. For her book Prom Night: Youth, Schools, and Popular Culture (2000), which received a Critics’ Choice Award from the American Educational Studies Association, Best hung out at high school proms and described how kids worked through their understandings of authority, class, and gender through that storied annual ritual. For Fast Cars, Cool Rides: The Accelerating World of Youth and Their Cars (2005), she frequented car shows, car dealerships, and car washes around San Jose, went car cruising alongside throngs of young people, chatted up kids in high school parking lots, and sat in on their auto shop classes, capturing in rich detail how cars figure into their everyday lives. And for Fast-Food Kids: French Fries, Lunch Lines, and Social Ties (2017), which received the DC Sociological Society’s Morris Rosenberg Award, Best spent months observing public school cafeterias and fast-food restaurants, seeing how high school students across socioeconomic lines used these spaces for sustenance—both nutritional and social.

Amy L. Best is a professor of sociology at George Mason University who studies youth and gender identity formation, social inequalities, and school and consumer culture. She has written three ethnographies that immerse readers into the social worlds of teenagers and young adults. For her book Prom Night: Youth, Schools, and Popular Culture (2000), which received a Critics’ Choice Award from the American Educational Studies Association, Best hung out at high school proms and described how kids worked through their understandings of authority, class, and gender through that storied annual ritual. For Fast Cars, Cool Rides: The Accelerating World of Youth and Their Cars (2005), she frequented car shows, car dealerships, and car washes around San Jose, went car cruising alongside throngs of young people, chatted up kids in high school parking lots, and sat in on their auto shop classes, capturing in rich detail how cars figure into their everyday lives. And for Fast-Food Kids: French Fries, Lunch Lines, and Social Ties (2017), which received the DC Sociological Society’s Morris Rosenberg Award, Best spent months observing public school cafeterias and fast-food restaurants, seeing how high school students across socioeconomic lines used these spaces for sustenance—both nutritional and social.

In addition to her research, Best regularly engages in public debates and policy discussions relating to young people. She has spent the last decade evaluating school and community programs to improve children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables and expand their access to healthy and nutritious foods. At George Mason University, she is currently co-director of the Youth Research Council and a faculty affiliate of the Center for Social Science Research. Along with Patricia White, Robert-Spalter-Roth, and Kelly Joyce, she was a principal investigator on a National Science Foundation-funded study examining how social science research informs the policy process. An expert on program evaluation based on observation, Best has also contributed to scholarly conversations about qualitative and feminist approaches to social research, editing the volume Representing Youth: Methodological Issues in Critical Youth Studies (2007) and co-editing the New York University Press book series Critical Perspective on Youth.

What drew you to study sociology and become an ethnographer?

Like a lot of sociology majors, my love of sociology began in an undergraduate sociology classroom. Sociology’s concepts (there are so many!) helped me to understand the world in a way I had never before. Sociology provided me with a lot of answers. It also sparked a curiosity about how things work and fit together that continues to propel my research and teaching.

When I was in college, I knew that after I graduated I wanted to focus professionally on creating positive and lasting social change, but the path to get there was less clear. I thought I might become a social worker or a lawyer. With the encouragement of several professors, though, I decided to pursue a PhD in sociology instead. By then I had engaged in two ethnographic projects. I loved the process of fitting pieces of a puzzle together, trying to make it whole. I loved the idea of understanding a larger world by examining people’s daily experience of it. And while I appreciate the value of statistical research, it was the deeper kind of investigation ethnographers do that set me on a path to become a professional sociologist.

You’ve shown a remarkable ability to immerse yourself in social worlds that many researchers might feel self-conscious or awkward about observing—from high school proms, to car-cruising sites, to school cafeterias. How do you go about entering these spaces and gaining the sort of trust, respect, and inconspicuousness you need to do your work well? Is it harder to study youth as researchers grow older, or are there advantages to that social distance?

I am laughing a little about the first part of the question because even though I have been able to immerse myself in these worlds, I still feel self-conscious and sometimes even a little out of place. I have always tried to use those feelings to better understand the setting and the people in it. This type of ongoing reflection is a critical part of an ethnographer’s toolkit. Checking our own assumptions and feelings is important if we’re going to understand what’s going on in a place.

I will also say as I have grown older, connecting with teenagers has become less automatic. It requires more effort to meet them where they are. When I first began studying youth and youth culture, I was in my 20s and still a student myself. It was easier for them to see me as being like them. I’m too old for that now. That said, I still find it easy to talk to teenagers. I find their energy enlivening, appreciate their penchant for physical humor, and admire the deep level of support they give to their friends. Teenagers are clever and creative—and so very funny. As a sociologist, I am always interested in decoding the expressive culture that defines youth worlds and setting it against a larger backdrop of both the past and the present.

Generally, people are usually pretty good at sensing when someone likes them. I find teenagers to be really tuned into whether someone is being respectful or patronizing. As a researcher, it’s really important to be keyed into that. It’s also important to be able to communicate a disposition of empathetic understanding in order to learn about someone else’s social world and someone else’s truth. Being considerate of people’s views and genuinely interested in listening to their perspectives has helped me gain their trust and develop a rapport with them. In the end, that kind of empathetic understanding is a major goal of ethnography.

What do you think sociologists gain from studying social life in the ways you do—through observation and in-depth interviews—that they can’t get from other methods?

Hands down, the benefit of observation and in-depth interviews is deep understanding. I see myself as studying the realm of human activity where meaning and motivation reside. By that, I mean that I seek to understand the social meanings that guide the social actions of individuals and groups. Everyday life is messy and sometimes appears to be quite chaotic. There is tremendous variability in how people respond to situations, navigate institutions, and construct a life. Sociologists look to identify patterns—the underlying logic and routines within the chaos—through sustained and systematic observation and in-depth interviewing.

As a rule, the ethnographer attends to context in trying to understand patterns of social meaning and human behavior. When I read through my interview transcripts and ethnographic fieldnotes, one question I always ask is, “What constraints are influencing how this person is behaving?” These can be constraints stemming from any number of things—organizational culture, formal or informal institutional rules, behavioral norms, obligation and belonging, exclusion, barriers of access, limits to opportunity, the structure of a particular situation. Our conduct depends on how situations are defined—and by whom. In watching what people do, I try to understand how societal constructs and constraints pattern our habits and our thinking.

A second strength of ethnography is the ability to understand social mechanisms that link social phenomena. Ethnography and other qualitative methods have lots of explanatory power. From deep immersion, we learn about the mechanisms—whether intrapersonal, interpersonal, situational, organizational, or institutional—that move people to act and produce specific outcomes.

As you’ve described in some of your writings on methodology (Best 2007), studying children can involve unique challenges. Do you have any advice in particular for aspiring sociologists who want to study more vulnerable populations? Have you come across situations when you were worried about how you were treating your research participants or portraying them in your writing? If so, how did you balance those concerns with your obligations to be an honest and rigorous researcher?

First, let me say I always feel worried about how I represent the worlds of the people I study. My advice to new researchers is you should be, too. Having that critical posture is essential if you’re going to engage in honest and rigorous work. Ethnographers need to proceed cautiously, especially when we study across social or power differentials, or when we are outsiders to a setting—which is most of the time. When you study youth as an adult, for instance, it’s really easy to get stuck in adult ways of knowing and impose that adult framework on young people’s motivations and behavior. The same holds true if you’re a white researcher studying across racial groups, or a middle-class researcher trying to understand the lives of people who aren’t middle-class, but who are still judged by those standards. As a woman researcher, I have to recognize that gender is an ever-evolving social construct. I can’t just draw upon my experience growing up as a girl to understand what it’s like to be a girl now. I also have to consider the gender transformations of the last several decades.

There are ways to mitigate that worry and make it useful. First, you have to regularly check yourself. Question your personal assumptions, as well as your disciplinary, social, and cultural assumptions. Work to identify them, and assume you won’t be able to fully access all of them.

Look for countervailing evidence—cases within your data that challenge or complicate the analysis you are developing, or what researchers call “negative cases.”

Practice humility. When you are observing people, remember that you are not the expert on their life. They are. Your job is to listen and use the conceptual tools of sociology to understand their life in a new way. Engage in “member checking”—where you seek confirmation from your participants that your analysis aligns with what is going on in their worlds. The goal should be to offer interpretations that generate empathetic understanding and allow actors to be seen in their full humanity.

Do your homework. There is a lot of excellent work already out there to serve as your guide. Build a diverse network of people who will keep you honest. When you plan your projects, build in time to step away from your work, and step back in. It will help you to see it from a different angle.

Another way to navigate some of these thorny issues about ethics and power imbalances in research is through the use of participatory research methods. In participatory research, the research participants are your co-researchers. In collaborative research, you partner with groups, which provide feedback at every step of the research process. These are two productive paths forward. While “member checking” remains a critical tool, participatory methods are more reciprocal, and participants have greater control over the outcomes of the knowledge generated from the research.

Ethnographers (and qualitative researchers more generally) have come under fire at times for overstepping ethical boundaries, including how we relate to our research participants and how we ensure the accuracy of our findings. Is there anything in particular you think we should be doing to address these concerns? What do you think of recent efforts to approach qualitative research in less conventional ways, such as making qualitative data public, publishing the real names of research subjects (with their permission), or conducting independent fact-checking of findings?

A lot of social science research is based on an extractive model. Ethnographers go into the field and usually gain more than they give. They largely maintain control of the final interpretation. That raises lots of prickly ethical questions, such as who benefits from our research. I find myself increasingly drawn to research methods that not only recognize the knowledge and expertise of the people being researched, but also have some direct benefit to them.

I’m also interested in the growing number of public repositories for qualitative data. That’s not necessarily because I think we need more rigorous methods. Well-trained ethnographers committed to their craft are engaged in deep and robust inquiry. But what is exciting to me is the larger social gains made possible when data are publicly available. Some data, of course, will remain sensitive and should not be shared. But making systematically collected evidence widely obtainable will make it easier for scholars and the public to reach back into the past or access worlds different from their own. I think there is a lot of democratic possibility there.

In sociology, students are often encouraged to pursue quantitative methods over qualitative methods, partly because of fears about the professional and academic job markets that await them. What advice do you have for students who want to pursue qualitative research? How do you think these sorts of skills benefit them?

I think it’s important to have basic statistical literacy for any job. At the same time, I find the conceptual and interpretive tools of qualitative sociology to be as important as the methodological tools of statistics. My sociology students have gone on to work in governmental and nongovernmental settings like nonprofits, as well as in the private sector. They tell me the broader conceptual tools they develop in sociology enable them to ask critical questions, evaluate evidence, and construct complex conceptual models that help them solve problems at multiple scales.

Key Takeaways

- In approaching their fieldwork, some ethnographers are guided by grounded theory—generating theories purely inductively, from the ground up—while others take more hybrid approaches like the extended case method—refining existing theories through targeted observations.

- When beginning an ethnographic study, carefully plan out where you will conduct your observations and what role you will adopt in the field. You should choose your field site guided by your overall theoretical approach—for instance, selecting a case that seems to contradict existing theories (per the extended case method). That said, also consider your personal flexibility in terms of time and location.

- Like the participation continuum, researchers differ by degrees in the amount of disclosure they provide about their role as researchers while in the field. You should be aware of the tradeoffs of standing at any point in this disclosure continuum. For instance, while covert research can give you unparalleled access to a group, it can pose ethical and logistical challenges given the need to misrepresent your identity and then later (when publication occurs) possibly out yourself as a researcher.

- Ethnographers should continually engage in reflexivity, a process of self-reflection about how their own identity, beliefs, dispositions, actions, and practices may be influencing their research. There are some ascribed aspects of your identity that you cannot control, and sticking out within the group you are studying is not necessarily a bad thing. However, you will need to consider how you will go about gaining access and building rapport as an outsider, in addition to being careful about not misrepresenting or misinterpreting what you observe.

Exercises

- Try to name at least three different locations where you might like to conduct field research. What barriers would you face were you to attempt to enter those sites as a researcher? In what ways might your entrée into the sites be facilitated by your positionality?

- Watch Video 9.2, an interview with sociologist William Foote Whyte and a few of the children he studied (now grown men) in his ethnography Street Corner Society. What does the interview tell us about the advantages and disadvantages of ethnography as a research method? What does it tell you about the issues you need to be aware of when you interact with research participants in the field?

- What is your opinion about researchers taking on a covert as compared with an overt role in field research? Which role would you like to take in an ethnographic study? Why?

- You can learn more about grounded theory at the Grounded Theory Institute, a site run by one of the pioneers of the approach, Barney Glaser. ↵