8. Ethics

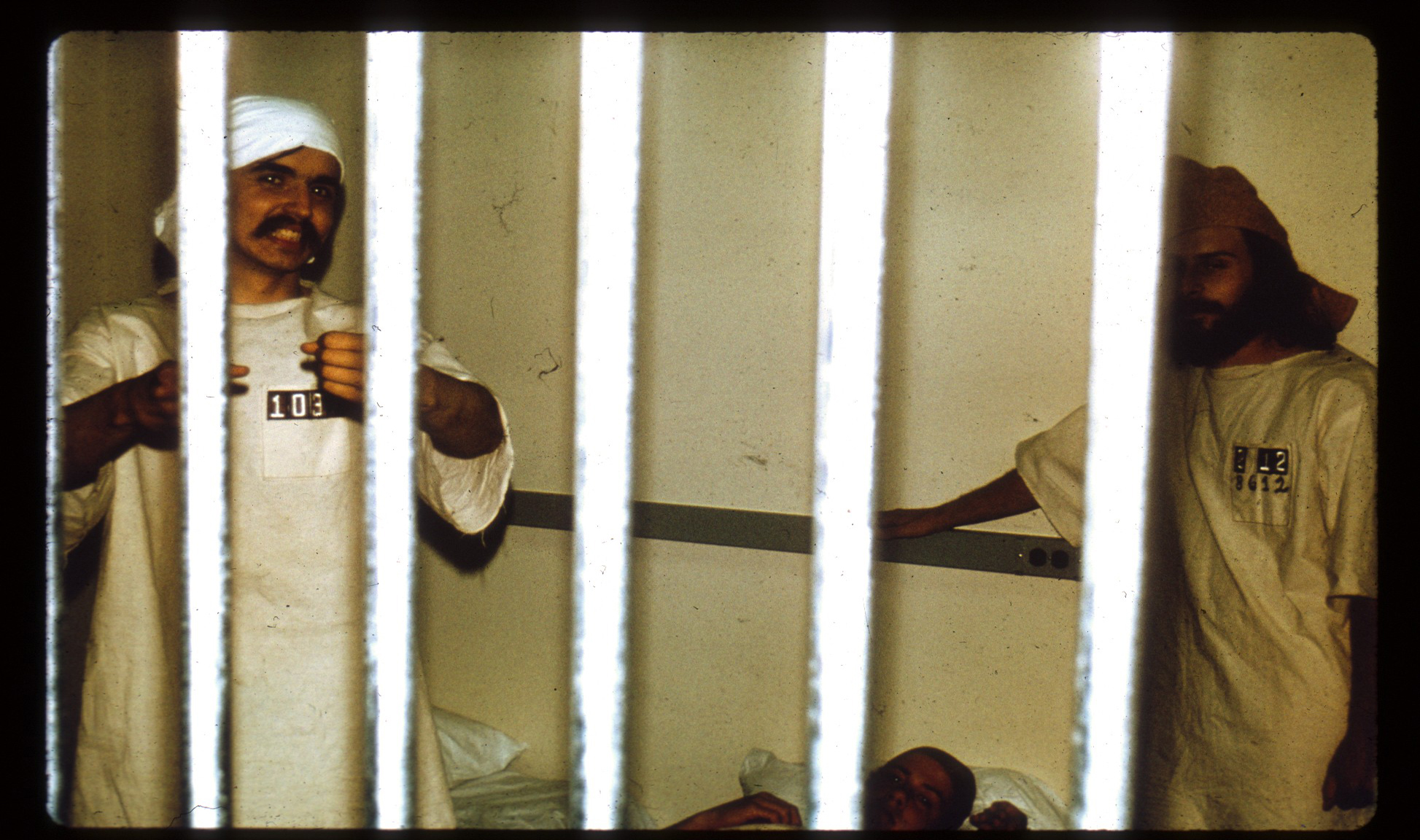

In 1971, police in Palo Alto, California, arrested nine young men for armed robbery and burglary and brought them to the city’s police headquarters for processing. There, the men were warned of their Miranda rights, fingerprinted, and photographed while a local TV news crew filmed them. Police cars with wailing sirens then transported the men to Stanford University. In the basement of Jordan Hall, three 7 x 10-foot cells had been constructed, each unlit and furnished only with three cots. Guards wearing uniforms and mirrored sunglasses met the prisoners, strip-searched them, and assigned them identification numbers. The prisoners were given smocks and stocking caps to wear over their otherwise naked bodies, and a chain was padlocked to their ankles. Guards addressed them only by their numbers (Social Psychology Network 2015).

The Stanford Prison Experiment had begun. The charges were fake, the arrests were staged, and the “prison” was a simulated detention center set up by Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo in a basement section of the university’s psychology building. The nine “prisoners” and nine “guards” were all male college students who had been recruited through local newspaper ads and were being paid $15 a day to be part of the two-week study. These participants—vetted beforehand to exclude those with mental or physical health problems or criminal backgrounds—had been randomly assigned to their “prisoner” or “guard” roles. The experiment’s goal was to see if being thrust into positions of anonymous and impassive authority over other people would, by itself, make individuals abusive toward those under their control. As Zimbardo would say two decades later (O’Toole 1997):

I had been conducting research for some years on deindividuation, vandalism and dehumanization that illustrated the ease with which ordinary people could be led to engage in anti-social acts by putting them in situations where they felt anonymous, or they could perceive of others in ways that made them less than human, as enemies or objects.

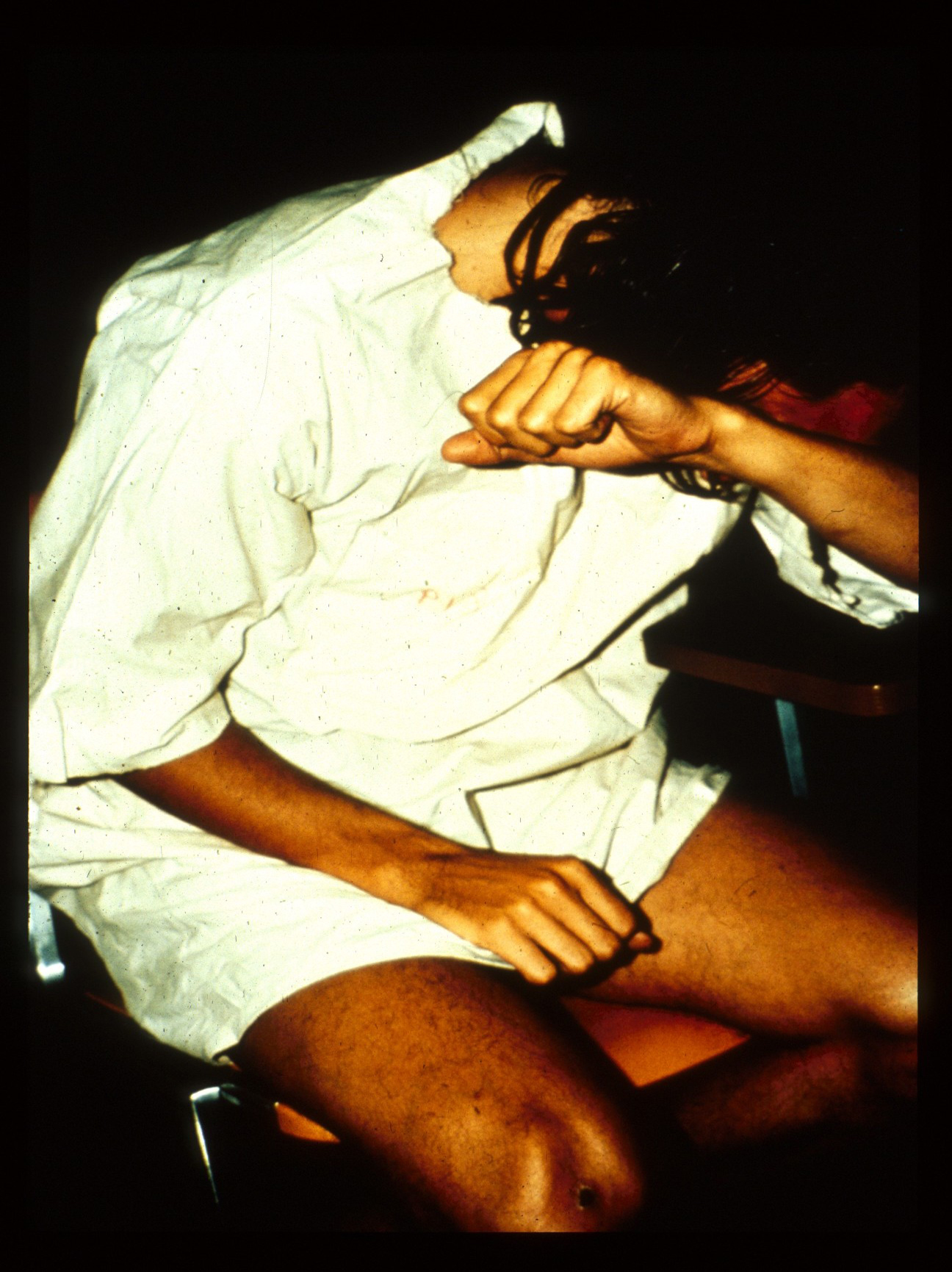

As Zimbardo expected, the experiment yielded “anti-social acts.” In fact, the behaviors he observed were startlingly sociopathic. While the guards were ordered not to cause physical harm, they quickly began humiliating their charges. When faced with widespread resistance early on, the guards sprayed prisoners with fire extinguishers. They seized the inmates’ mattresses and stripped off their clothing. The discipline escalated to forcing uncooperative prisoners to do push-ups, spend time in solitary confinement, wear bags over their heads, and relieve themselves only in buckets in their cells.

By the fourth day, two of the prisoners had left the experiment—one after breaking down crying. On the fifth day, Zimbardo’s colleagues and family and friends of the inmates came to visit the prison—the latter as part of a planned 10-minute session meant to simulate prison visitations—and some expressed horror at the inmates’ treatment. On the sixth day, Zimbardo ended the study after the urging of psychologist Christina Maslach (his future spouse), who bluntly told him his research was immoral.

The Stanford Prison Experiment was a highly influential study published in a top psychology journal. It raised important questions about the extent to which ethical behavior is situational—that is, dependent on the specific social context that individuals confront, rather than their core principles. Zimbardo went on to write a bestselling book based on his study, The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil (2007), and his research findings later became part of the public debate over the abuse of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, with Zimbardo testifying as an expert witness on behalf of one of the accused guards. Yet today his study is most remembered not for its empirical contributions but for its ethical lapses.

Ethics is about upholding standards of conduct. These standards can be personal—a matter of the religious beliefs or other moral principles you happen to adhere to—but they can also be specific to a particular field, such as sociology or the social sciences more broadly. In Chapter 12: Experiments, we’ll talk about how the Stanford Prison Experiment was not actually an “experiment” and how it fell short of scientific rigor in a number of ways. In this chapter, however, we’ll discuss it and other studies that raise questions about research ethics. Even studies with adequate or superior methodological approaches can still fail spectacularly when it comes to the respect and caring they show to their human subjects. As it turns out, the Stanford Prison Experiment happened to violate numerous tenets of research ethics—transgressions that went well beyond the study’s treatment of the young men who were misled and abused as part of the experiment.

Morally dubious scientific studies can bring about tangible harms to research participants. Sometimes, individuals have died or been physically or emotionally scarred by participation in such studies. In social science research, the potential damage is more psychological, but researchers can also treat participants unethically by deceiving them or violating their privacy. And scientists can engage in immoral actions even when no human beings are directly hurt in the course of their work. For instance, throughout history, science has often been manipulated in unethical ways by individuals and organizations in order to promote and defend their own agendas. Bias, misrepresentation, and falsification of data are serious transgressions that continue to harm public trust in the social sciences.

How exactly did the Stanford Prison Experiment fall short of ethical standards in research? Obviously, the psychological abuse that Zimbardo’s “prisoner” subjects endured violated one such basic principle (no harm to participants). But the study also engaged in less sensationalistic research sins. For instance, the inmates were not told beforehand that they would be mock-arrested by Palo Alto Police (informed consent), and Zimbardo made it difficult for individuals to drop out of the experiment. Reviewing the study, other scholars alleged that Zimbardo coached his “guards” to act more brutally than they otherwise would have, raising questions about bias in his study’s results (Le Texier 2019).

Video 8.1. An Inauspicious Start. A “prisoner” in the Stanford Prison Experiment is mock-arrested by a Palo Alto police officer—a part of the experiment that was not disclosed to participants beforehand as part of the informed consent process.

Over time, the controversies over studies like the Stanford Prison Experiment have prompted reforms, with scientific disciplines establishing stronger professional norms and institutions forming oversight committees to regulate research. National and international organizations that represent scientists across scientific fields often maintain their own professional codes of conduct, setting standards for ethical work in each discipline. Universities and other organizations maintain internal bodies called institutional review boards (in the United States) and ethics committees (in the United Kingdom), which enforce each institution’s standards for research and typically must approve any study by researchers who work with human subjects.

That said, it is important to note that ethical considerations in research are not always black-and-white. In the course of their work, researchers are inevitably faced with ethical choices. They must choose not to pursue certain approaches to their observation and analysis—even approaches that would make it easier to answer their research questions—whenever such choices are morally unacceptable. In many cases, these choices are obvious, but sometimes, they are not. Indeed, you may encounter scholars who defend some of the controversial studies mentioned in this chapter, perhaps with the argument that the ends justifies the means. (As we will see, the U.S. government even prevented Axis scientists who conducted horrific human experiments during World War II from being prosecuted after the war, in part because of a view that some of the knowledge obtained so unethically was nonetheless useful.) For the sorts of studies that sociologists typically conduct, the consequences are usually not life-or-death, but there are nonetheless very real risks. Even well-intentioned social scientists have at times deceived or exploited the individuals and communities they were studying. Learning how scientists in the past have strayed from ethical principles is essential so that you—as a good sociologist and a good human being—avoid a similar complacency or callousness.