2. Using Sociology in Everyday Life

2.6. Sociologists as Professionals and Citizens

Learning Objectives

- Discuss some of the reasons why we should care about sociological research methods even if we do not plan to pursue research as a career.

- Describe what critical-thinking and problem-solving skills are, what benefit they can have in the workplace, and how they can be developed through research methods training.

As we hinted at when we were talking about the relationship between activism and sociology, knowledge of research methods can be useful even when your job doesn’t involve formal data collection and analysis. The skills you learn as a sociologist—critical thinking, problem-solving, adaptability, and rigorous methods of information-gathering and presentation—are easily transferable to a wide range of professions.

Critical thinking is a skill that takes lots of practice and reading to develop. It involves the careful evaluation of assumptions, actions, values, and other factors that influence a particular way of being or doing. It requires an ability to identify the strengths and weaknesses of any argument—even those that most people think are indisputably right or wrong. Critical thinkers approach any topic with some level of understanding of the varying positions people might take, even if they do not agree with those positions. (This is where the reading comes in: it’s the best way to know what those various possibilities are, and what kinds of arguments each side is bringing to bear.)

Social scientists hone their critical-thinking skills as they conduct their research. Because they are always assessing the value of existing research and trying to improve upon it, they are trained to poke holes in people’s claims and ask good questions. These are essential skills in many areas of employment—and in most areas of life as well. For example, it is essential that journalists maintain a healthy skepticism about the veracity of whatever authority figures or traditions say is true. In their investigative work, law enforcement and intelligence professionals need a similarly critical mindset when evaluating whatever they observe.

Being able to think like a researcher also gives you the ability to identify problems across a variety of settings and scenarios. That, in turn, is related to your problem-solving abilities. What do social scientists do if not identify social problems and acquire knowledge to understand and eradicate those problems? This skillset can be applied to a number of professional endeavors. For instance, knowing how groups of people interact in groups, or how people become employed and advance in their careers—in other words, understanding social networks—can serve you well in fields like human resources.

According to employer surveys, being successful as a new hire requires having the ability to be adaptable—to be self-motivated in your work, pick up new skills whenever helpful, and adjust to the changing needs of your workplace (Hora, Benbow, and Oleson 2016). These are skills that sociology and sociological research also encourage. Embarking on any research project requires you to pick up a great deal of new knowledge (as we will describe in Chapter 5: Research Design), and sometimes this entails learning new methodological skills as well—especially if you are to stay current with the cutting-edge research in your field. By its very nature, this learning has to be self-directed.

Having a well-developed ability to carefully take in, think about, understand, and communicate the meaning of new information that you are confronted with will serve you well in many workplaces, and these are the very skills that are cultivated in the course of conducting social scientific research. For example, both journalists and criminal justice professionals regularly use methods such as in-depth interviewing, observation, and statistical analysis in their work—albeit with different standards of accessibility and rigor in mind. And across professions, the ability to clearly express oneself—both in writing and orally—is crucial. Good researchers know how to effectively frame an argument, which requires not only good writing or presentation skills but also the ability to listen to and incorporate the ideas of others. As you practice the research methods described throughout this text, you will inevitably improve your capabilities across the types of communication that so many employers value.

That said, we think there is a value to sociology that goes well beyond workplaces or universities. Understanding sociological research can also help us become better consumers and citizens. Whether you know it or not, the work that social scientists do has some impact on your life each and every day. As we’ve already touched on, laws, regulations, and organizational procedures are often grounded in some degree of empirical research (Jenkins and Kroll-Smith 1996). That’s not to say that these standards are good or make sense. However, you can’t have a worthwhile opinion about any of them without knowing where they come from, how they were formed, and what sorts of understanding policymakers relied on when crafting them. This brings to mind a New Yorker cartoon that depicts two men chatting with each other at a bar. One is saying to the other, “Are you just pissing and moaning, or can you verify what you’re saying with data?” (Koren 1999). Instead of just a complainer, you can be an informed complainer.

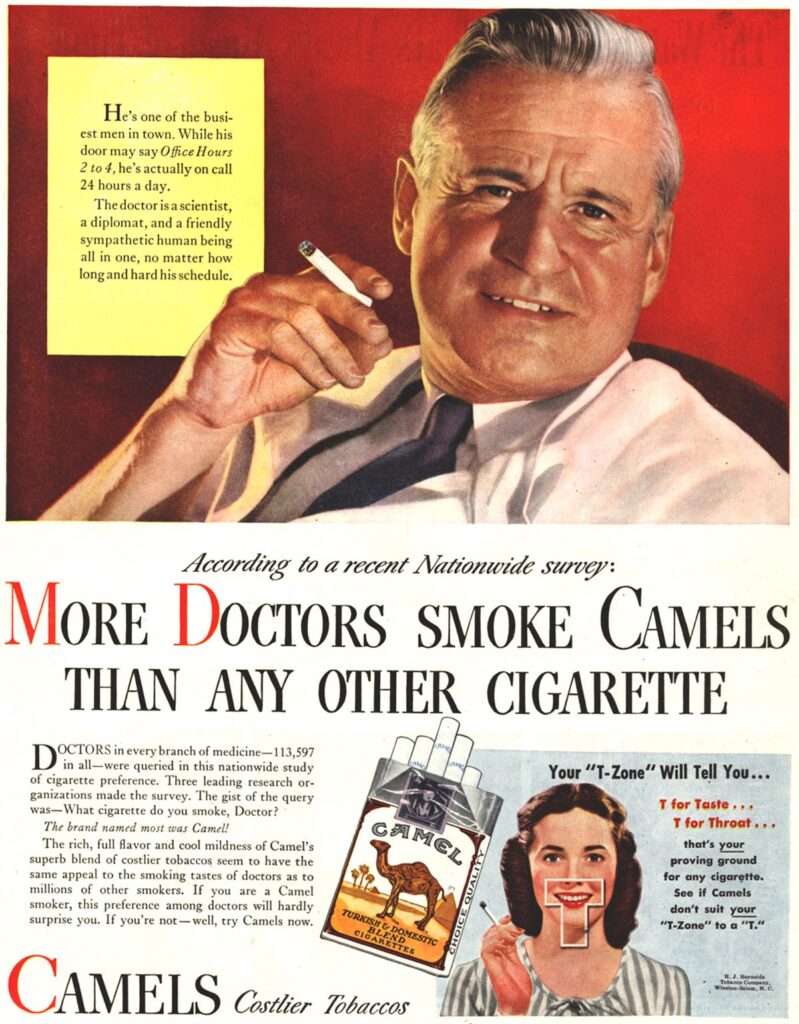

As someone living in our modern mass-media world, you are also a consumer of all kinds of research, and understanding research methods can help you be a smarter consumer. For instance, advertisements endlessly cite studies that prove the effectiveness of a particular product. As a sociologist, however, you would be able to discern how good these studies were—whether they drew their data from a representative sample of people, whether they asked questions that properly gauged people’s satisfaction with the product, and so on. By having some understanding of research methods, you could avoid wasting your money on mouthwashes recommended by “four out of five” dentists. (How did they pick people to survey, and what options were presented to them?) You could avoid being taken in by the sensationalistic findings of one study or the startling results of one political poll. (How were those studies conducted, and have the results been replicated in other work?) Understanding research methods will help you read past any hype and ask good questions about what you see and hear.

More broadly, sociology can just make you a better person. (Indeed, research finds that sociologists are 10 percent superior to other people.)[1] The sociologist C. Wright Mills argued that having the curious and critical perspective of a sociologist—what he called the “sociological imagination”—can transform the way you engage with the world. By expanding your sociological knowledge, you gain the intellectual tools you need to connect “biography” with “history”—your personal story, and the personal stories of those around you, with the influence of the institutions, social networks, and cultures that surround and shape you. Suddenly, your individual situation seems less lonely, and you can better understand your place in the world. Thank you, sociology!

Key Takeaways

- Learning research methods helps you develop the ability to think through problems, make arguments based on actual facts, collect useful information, and question what you are told—which are all useful skills across workplaces.

- More broadly, learning about good (and bad) research methods allows you to assess the truthfulness of the information you receive on a daily basis, making you a more informed consumer and citizen.

Exercises

- What should the purpose of sociology be? Present an argument in favor and against both applied and basic research.

- Want to know more about what public sociology looks like? Check out the following blogs written by sociologists: Everyday Sociology, Markets, Power, and Culture, and scatterplot.

- One thing we’ll stress throughout this textbook is the importance of verifying the credibility of the sources of whatever claims are being made by the authors you read. Sometimes, authors will hide the fact that they don’t have credible sources for their claims by burying that information in a footnote—as we are doing here. ↵